THE OLMEC LEGACY: Part 2

START at 7:26

STOP at 7:26

What is the most recognizable characteristic of the Olmec? (Hint: Use your head!)

Where did the Olmec get the rock for their huge sculptures?

The Olmec moved their sculptures long distances and over rough terrain. How did they do it?

Are these huge sculptures the Olmec gods and goddesses?

On the US mainland, where might you find a replica of an Olmec head?

The Olmec “altars” aren’t altars. What are they?

Why were caves important to the Olmec peoples?

What does “The Wrestler” tell us about Olmec artists?

We have were-wolves. What did the Olmec have?

List three or more of the Olmec gods.

• READ •

THE OLMEC LEGACY: Part 2

The Olmecs are best known as the creators of Mexico’s first civilization,

and for making some of the country’s most extraordinary works of art.

Olmec Art

Nothing highlights the Olmec better than their distinctive and recognizable art. Their most iconic and well-known works are by far their colossal heads.

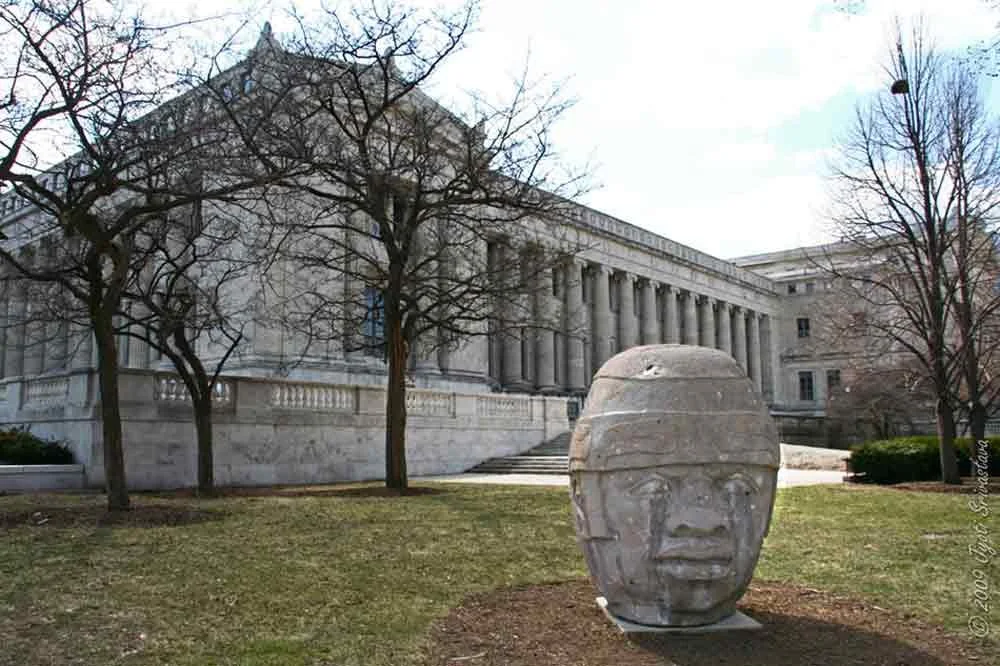

Even if you've never studied the Olmec, you've probably seen pictures of them in a textbook or on TV. These heads are gigantic. Each one is carved from a huge block of basalt.

The nearest source of this is all the way in the Tuxtla Mountains, which means that they had to not only be carved but moved huge distances. Remember there are no draft animals in Mesoamerica. You can't just strap some oxen and mules to those boulders and tell them to move.

They could only be moved by human labor.

• Tuxtla Mountains

The organization and effort to move these from quarries to the cities and ceremonial centers must have been enormous. As far as we know they could have been dragged overland or perhaps transported on balsa rafts via the local rivers, but no one is certain.

But what are these sculptures exactly?

Most scholars agree that these heads represent Olmec rulers, as each one is distinct and none portray the same person. Each head has a helmet or headgear. The heads are very recognizable for their realism and their broad facial features like their flat noses and full lips.

These striking features have actually caused some to theorize that the heads are sculptures of Africans, but these theories are rejected by Mesoamerican scholars and I'll have more to say about these views later.

In total there are 17 heads that have been discovered at various Olmec sites.

These range in size from just under 5 feet to 11 feet tall. The largest head is over 25 tons. To put that in perspective, that's more than the weight of two school buses.

One interesting thing I discovered while making this episode is that there are actually several replica Olmec heads across the United States.

• Olmec head replica at Field Museum in Chicago

If you ever pay a visit to the Field Museum in Chicago, City College of San Francisco, Lehman College at the City University of New York, the Smithsonian, or the University of Texas in Austin, you can see one of these replicas. Pretty cool.

Altars

As impressive as the Olmec heads are, they were not the only colossal sculpture crafted by the Olmec. They also carved massive stone altars, each from a single block of basalt weighing over 40 tons.

Actually the term "altar" is a bit of a misnomer. When these were first excavated they were believed to be altars, but experts are pretty certain that these huge blocks were actually thrones for rulers. The reason for this is that there are actually images and sculptures of rulers sitting on these altars.

Each throne contains a niche with a man sitting in a cave, either holding a baby with jaguar features or a rope, sometimes both.

In many later Mesoamerican cultures, caves are an entrance to the supernatural world, so this imagery is very evocative. Remember this because caves are going to come up later in the episode.

As these monuments show, the Olmec were masters at shaping stone, and these monuments are only the tip of the iceberg.

One of the finest examples of Olmec sculpture is "The Wrestler."

This seated figure is portrayed in a realistic and dynamic way that is seldom seen in Mesoamerica.

Another important piece comes from a burial in La Venta. This group of small jade figurines were found posed around a central figure in a very striking scene.

• Olmec jade figure

No one is certain what this is depicting, but it definitely fires up the imagination. Is this a scene from Olmec mythology? A ruler's court? Or a scene from the deceased's life?

We don't know, but it is pretty cool to think about.

Were-Jaguars

Olmec art is one of the best tools we have in reconstructing their religion and their beliefs. When we examine Olmec art with knowledge of later cultures, we can see important religious concepts taking shape.

Remember those babies from the thrones we just talked about? Let's take a closer look at those babies.

Abundant in Olmec art, usually on the chubby side, many of these babies, just like the ones on the thrones, have jaguar features. This is a very common theme in Olmec art and scholars call these babies "were-jaguars" - like werewolves but instead were-jaguars.

These depict people that are in the process of transforming into jaguars. They have snarling fanged mouths, upturned lips, and sometimes even claws. These images are not just limited to children.

There are also examples of adult transformations as well as transformations into other animals like birds, sharks, and crocodiles, but were-jaguars are the most common. They appear in ritual axes carved from green stone and other materials.

Were-jaguars occupied an important place in Olmec religion and it's believed that some of these were-jaguars are shamans in a state of transformation.

Shamanism was an important element in Olmec and later Mesoamerican religions. They are not unique to Mesoamerican culture - you can find shamans in many parts of the world even today.

Shamans interact with the spiritual world by taking hallucinogens to enter an altered state of consciousness. In this state, Olmec shamans could transform into animal spirits and enter the supernatural world, and through it influence the real world.

A shaman might want to influence the growth of crops or the coming of rain to sustain his people. Shamans were very important people in the Olmec community and it's no wonder that we find so much representation of them in their art.

Mesoamerican Gods

However, some of these were-jaguars also show us a picture of proto-deities that will appear in later Mesoamerican religions.

One piece that exemplifies this is the Las Limas figure - the sculpture of a man holding yet another were-jaguar baby.

• The Las Limas figure

But what makes it significant are the inscriptions carved into the man's body. It's very hard to see in this picture, but there are four icons carved into his shoulders and knees.

Scholars have pointed out that these icons have distinct features later associated with Mesoamerican deities. These features are very diagnostic and we can use them to identify specific later deities.

For example, on his right shoulder we have Xipe Totec, the god of spring and regeneration. He's also known as the Flayed God. On the left we have what is believed to be the Fire God or the Fire Serpent as he's also known. On the left knee we have the God of Death.

• From La Venta (1200–400 BCE), the earliest known representation of a feathered serpent in Mesoamerica.

On the right knee is the Feathered Serpent, known more commonly by its Aztec name Quetzalcoatl and by the Maya as Kukulkan.

He's gonna be a big figure in later Mesoamerican religion.

The cradled infant has been identified as the Maize God due to the decorated band above his head.

Here's another image of a were-jaguar maize god. These are some of the earliest images we have of the Mesoamerican pantheon. These show that important deities had their origin among the Olmec.

But gods aren't the only elements of Mesoamerican mythology depicted in Olmec art.

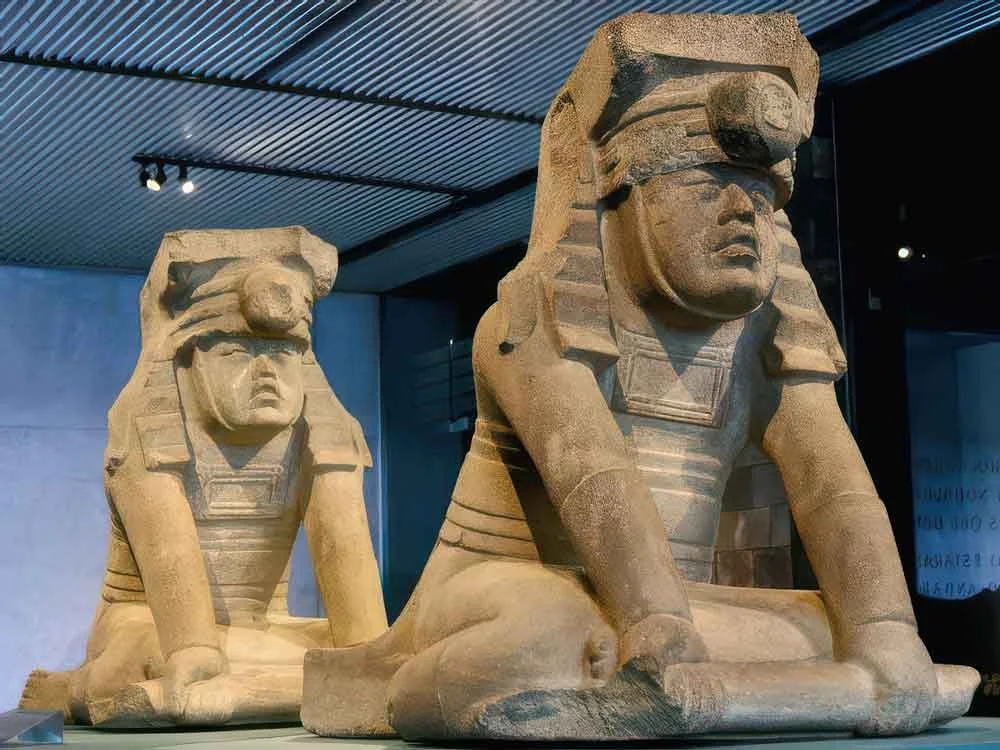

At the Olmec site of El Azuzul, archaeologists unearthed two statues of identical twins.

For anyone familiar with the Maya creation story, the Popol Vuh, these identical twins should be ringing a bell. These are believed to be the Hero Twins from the story.

Twins feature very prominently in the heroic literature and art of Mesoamerica, but this is one of the earliest examples we have of a depiction of twins. Again, when we talk about Mesoamerican mythology in later episodes, think back to the Olmec and think back to this sculpture.

One final religious practice that appears to have its origin in Olmec culture is bloodletting.

An intact tomb at La Venta contains a stingray spine and other instruments that many scholars believe were used to draw blood.

Bloodletting, or auto-sacrifice as it's also called, played an important role in later Mesoamerican religions. By offering up their blood, rulers and priests could ritually contact their revered ancestors and ask for their intercession in the spiritual world.

This was a vital element of kingship during the later Classical period and we're going to see it come up again.

Basalt - A hard, dark volcanic rock used by the Olmec for carving their giant sculptures

Colossal - Extremely large or gigantic in size

Deity - A god or goddess worshipped by people

Diagnostic - Features that help identify or recognize something specific

Evocative - Something that brings strong images, memories, or feelings to mind

Hallucinogens - Substances that cause people to see or experience things that aren't real

Intercession - Asking for help or speaking on behalf of someone else

Misnomer - A wrong or unsuitable name for something

Niche - A small hollow or recessed space in a wall or sculpture

Proto-deities - Early forms of gods that would later become more developed

Quarry - A place where stone is dug out of the ground

Shaman - A person who acts as a bridge between the physical and spiritual worlds

Supernatural - Related to things beyond the natural world; magical or spiritual

Transformation - The process of changing from one form into another

Were-jaguar - In Olmec art, a figure that is part human and part jaguar

► COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

— please answer with complete sentences

What is the most recognizable characteristic of the Olmec? (Hint: Use your head!)

Where did the Olmec get the rock for their huge sculptures?

The Olmec moved their sculptures long distances and over rough terrain. How did they do it?

Are these huge sculptures the Olmec gods and goddesses?

On the US mainland, where might you find a replica of an Olmec head?

The Olmec “altars” aren’t altars. What are they?

Why were caves important to the Olmec peoples?

What does “The Wrestler” tell us about Olmec artists?

We have were-wolves. What did the Olmec have?

List three or more of the Olmec gods.