Do Birds Have Language?

How do (human) babies learn to talk?

Chimpanzees cannot learn language like humans. What animals can?

In addition to repeating sounds, what else can birds do with birdsong?

All zebra finches’ songs do not sound the same. Why not?

What animals can Japanese tits (a kind of bird) identify with their song?

Name another bird that can identify predators with song.

Hard question: What is syntax?

What suggests some animals have a purpose when vocalizing (making making sounds)?

What have scientists learned from studying Arabian babblers?

Hard question: What is evolutionary convergence?

• Read •

Do Birds Have Language?

Bird Talk

Have you ever listened closely to birds singing? You might think they’re just making noise, but scientists believe some birds may be doing something much more amazing — something a lot like talking!

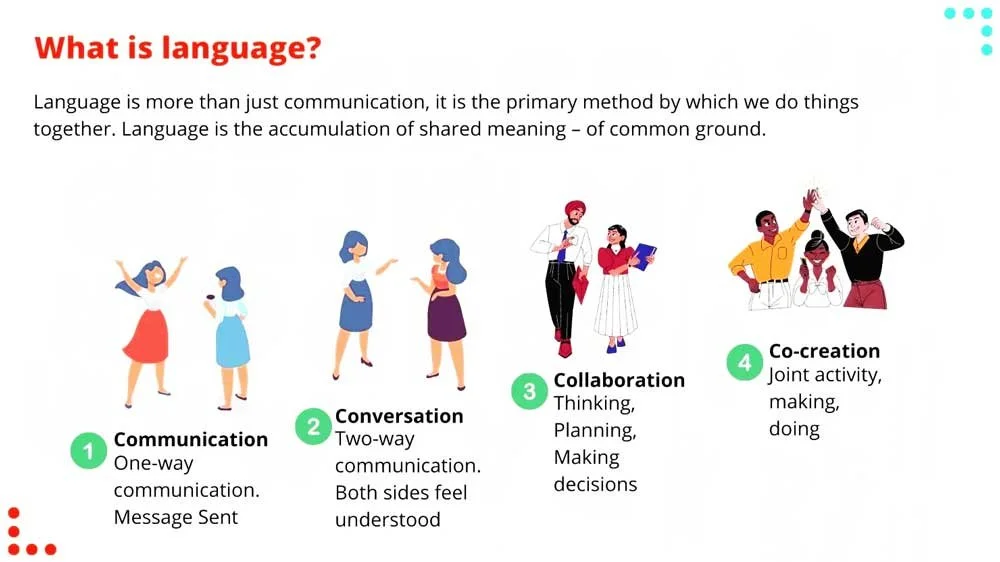

Humans are pretty special when it comes to language. Babies learn to speak by listening, remembering, and then trying to copy what they hear. This is called vocal learning.

Most animals can’t do this — not even monkeys, who are our closest relatives. But some animals far away from us on the family tree, like dolphins, bats, and especially birds, can learn sounds the way we do.

Parrots, songbirds, and hummingbirds are all great at vocal learning.

Some even use their sounds in ways that remind scientists of how we use words. Birds don’t just repeat sounds — they might use them to give information, show feelings, or even follow simple rules, just like we do in human language.

Birdsong and Culture

One scientist, Julia Hyland Bruno, studies zebra finches — little birds that travel in groups and learn songs from each other.

• Zebra finches

These birds don’t just learn on their own; they copy sounds from other birds around them, almost like how people learn songs or words from their families and friends.

Over time, groups of birds in different places might change their songs a bit, creating different “dialects.” That’s a lot like how people in different parts of the world speak in different ways.

This kind of learning from others is called cultural transmission. It’s one reason some scientists think bird communication has a lot in common with human language.

Calling With Meaning

A big part of human language is connecting words to meanings.

We don’t just make noise — we say things on purpose. Scientists used to think animals only made sounds when they were feeling something, like fear or anger. But now we know that birds and other animals can make sounds that mean very specific things.

For example, Japanese tits (a kind of bird) use one sound to warn about crows and a different one for snakes.

• Japanese tit

Each sound causes baby birds to react in the right way — hiding or jumping out of the nest! Other birds, like Siberian jays and chickadees, also have special calls depending on the kind of predator nearby.

• Siberian jay

Some birds even change how many sounds they use depending on how dangerous the threat is.

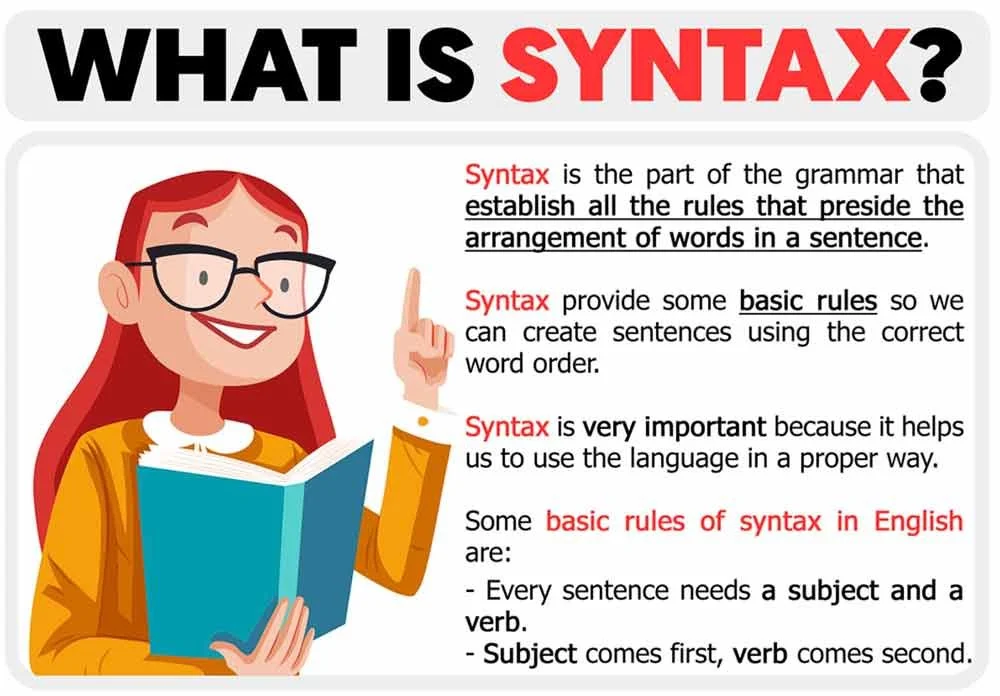

Even more interesting, some birds seem to combine calls in a certain order to send a clearer message. If you switch the order, the meaning might change — kind of like how “dog bites man” is different from “man bites dog.”

That’s something scientists call syntax — the order of words or sounds.

Do Birds Know the Rules?

A team led by scientist Toshitaka Suzuki tested how much birds care about the order of their calls. They found that Japanese tits reacted more strongly to one order of calls than the same calls in reverse.

• Japanese tit

That means birds may understand that order matters, just like we do when we speak.

Still, not all scientists agree that bird communication works the same way as human language. One researcher, Adam Fishbein, thinks people sometimes try too hard to make bird sounds fit into human language rules.

The Sounds Birds Hear

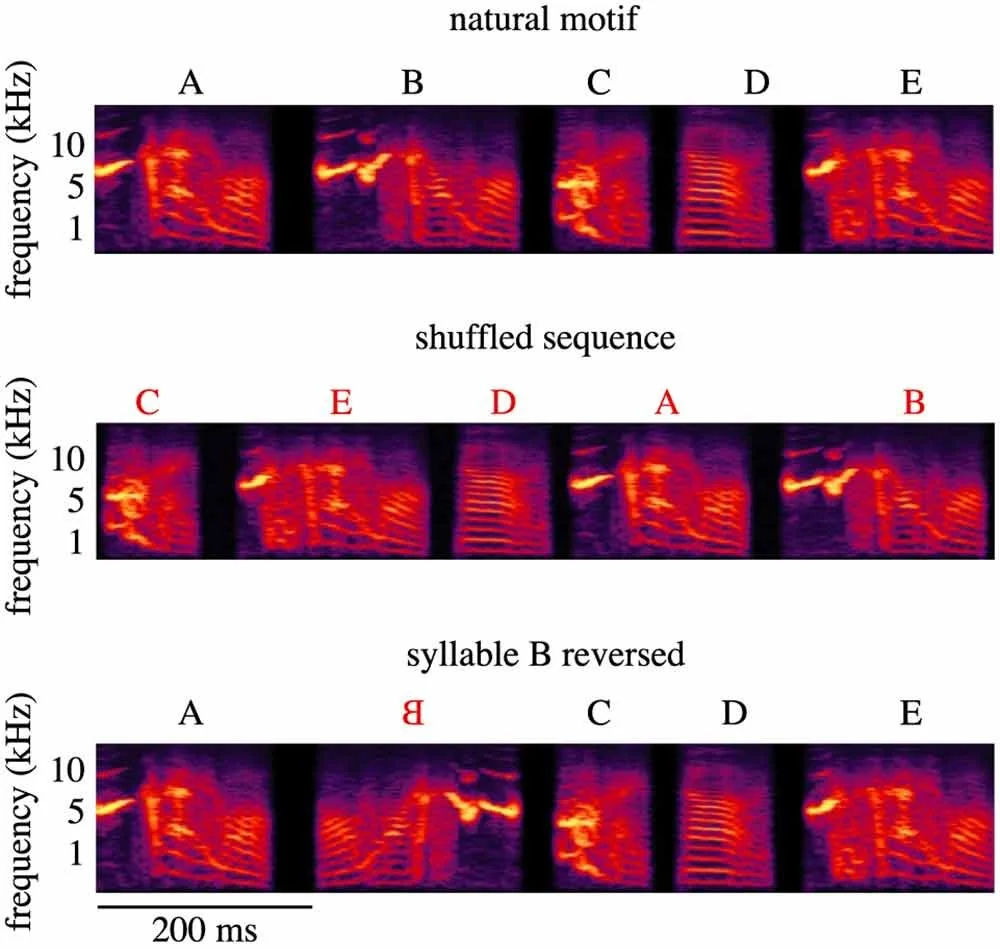

Birdsong is often full of repeating patterns, and to us, it sounds like music or even words. But what do birds actually hear?

Fishbein studied zebra finches by teaching them to press a button when they noticed a change in the song. If they were right, they got food. If they were wrong, the lights went out. When scientists changed the order of sounds in the song, people could hear it easily, but the birds didn’t seem to notice.

But when the scientists changed the fine details inside a single sound — by playing one syllable backward — the birds caught it right away.

This shows that birds may be paying attention to different parts of the sound than we do. What’s important to us might not be what matters most to them!

What Are Birds Thinking?

Even if some birds use sounds in ways that are like human language, we still don’t know what they’re thinking. Do birds make sounds just because they feel like it, or do they really mean to send a message?

Some animals change what they “say” depending on who is listening.

For example, a dog might bark to get a person’s attention, or a raven might hold up an object to show another raven. These actions show some animals may have a purpose when they communicate.

• Arabian babbler

In Israel, scientists studied Arabian babblers — birds that live in the desert. When parents wanted their babies to move to a new shelter, they called to them and flapped their wings. If the baby didn’t follow, the adult came back and did it again.

This showed they were trying to teach or persuade the young birds. That kind of behavior may be a sign that birds understand how others think — or at least that they’re trying to send a clear message.

A Brain for Sound

Here’s one of the wildest parts of the story: Birds and humans are not closely related at all. Yet, both have a special brain circuit that helps them learn and copy sounds. Our closest relatives, the monkeys, don’t even have this.

Scientists think this ability evolved separately in birds and humans. That’s called evolutionary convergence — when different animals develop the same skill in different ways. It’s like if two kids who never met both invented skateboards on their own.

• Evolutionary convergence

Erich Jarvis, a scientist who studies bird brains, believes the sound-learning part of our brain came from a section that first helped animals move their bodies. Over time, it changed into something that helps with learning to speak or sing.

So... Do Birds Have Language?

Well, it depends on what you mean by “language.”

If you’re thinking of full sentences and conversations, birds probably don’t have that.

But if you mean using sound to share information, warn others, or even “speak” on purpose — birds may be doing more than we ever thought.

They’re not just singing for fun. They might be saying something, after all.

Alert (adj.) – aware of danger; watchful

Analogous (adj.) – similar in some way

Circuit (n.) – a system or pathway that carries signals in the brain

Cultural transmission (n.) – the passing of knowledge or behavior from one generation to the next

Dialects (n.) – different ways of speaking the same language

Evolutionary (adj.) – related to how living things change over time

Forebrain (n.) – the front part of the brain that controls thinking and learning

Intentionality (n.) – the quality of doing something on purpose

Motif (n.) – a repeated pattern in music or sound

Neuroscientist (n.) – a scientist who studies the brain and nervous system

Perceive (v.) – to notice or become aware of something

Predator (n.) – an animal that hunts other animals for food

Recruitment (n.) – the act of bringing others together for a task or group

Remnant (n.) – a small leftover part of something

Rendition (n.) – a version or performance of something

Rudimentary (adj.) – basic or not fully developed

Semantics (n.) – the meaning of words or phrases

Syllable (n.) – a part of a word that has a single sound

Syntax (n.) – the rules for how words are arranged in a sentence

Vocalization (n.) – a sound made by the voice

► COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

— please answer with complete sentences

How do (human) babies learn to talk?

Chimpanzees cannot learn language like humans. What animals can?

In addition to repeating sounds, what else can birds do with birdsong?

All zebra finches’ songs do not sound the same. Why not?

What animals can Japanese tits (a kind of bird) identify with their song?

Name another bird that can identify predators with song.

Hard question: What is syntax?

What suggests some animals have a purpose when vocalizing (making making sounds)?

What have scientists learned from studying Arabian babblers?

Hard question: What is evolutionary convergence?

► From EITHER/OR ► BOTH/AND

► FROM Right/Wrong ► Creative Combination

THESIS — Argue the case that only human beings have language.

ANT-THESIS — Argue the case that other animals, like some birds and dolphins, have language.

SYN-THESIS — How might both perspectives be true?