The Secret History of the Potato

• You don’t need to remember any details from the video!

• You will need to read text below!

How many years ago did potato evolution start?

Did human beings engineer the evolution of the potato?

Where (on Earth) do potatoes come from?

What two plants are the “parents” of the potato?

What are tubers?

Why were tubers important to the survival and success of the potato?

Today, about how many species of potato are there?

How is the movement of tectonic plates and the evolution of the potato connected?

How do most farmers grow potatoes? (Hint: They do not plant potato seeds!)

Why might a new disease wipe all potatoes out?

• Read •

The Secret History of the Potato

long long ago…

When you eat a French fry, a baked potato, or mashed potatoes, you're biting into a food with a surprising past.

Scientists recently discovered that the potato, one of the world’s most important foods, is the result of an incredible twist of nature that happened about 9 million years ago.

That’s right—millions of years before humans even existed, a wild tomato-like plant and a potato-like plant teamed up to create something new.

That new plant became the ancestor of every potato we eat today.

A Wild Beginning in the Andes

The potato's story begins high in the Andes mountains of South America.

It was there that a plant from the tomato family met a rare plant called Etuberosum. Neither of these plants could grow potatoes as we know them. But together, they formed a hybrid—a mix of both plants—that could.

• Etuberosum (left) are potato-like plants that don’t grow tubers.

• Potatoes (right) evolved to grow tubers.

This plant mix-up wasn’t planned.

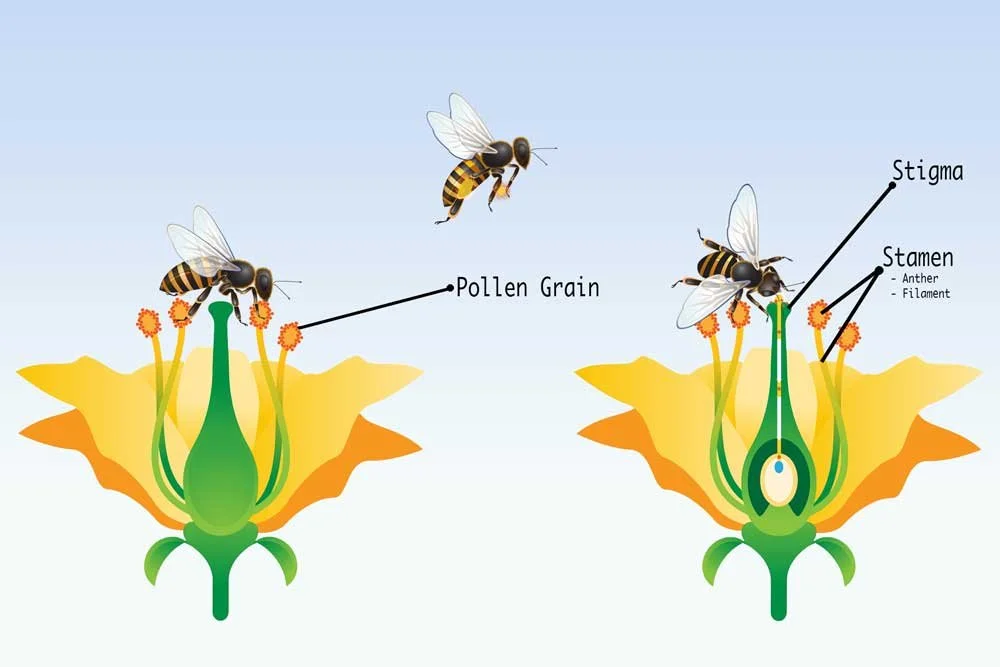

Scientists believe a bee carried pollen from one plant to the other. The new plant had a powerful combination of genes. From the tomato side, it got a gene called SP6A, which acted like a master switch, telling the plant to make tubers.

Tubers are the thick underground parts of a plant that store nutrients.

From the Etuberosum side, it got a gene called IT1, which helped the underground stems grow. Without both of these genes, the potato would never have existed.

Tubers to the Rescue

Why are tubers so important? They let the plant store water and food underground. This helped the potato survive in the Andes, where the weather is dry and cold.

While other plants needed seeds or flowers to grow, potatoes could just sprout from their tubers. That made them tough, dependable, and ready to grow in hard places.

Over time, wild potatoes spread across South America, adapting to different environments—from rainforests to rocky mountainsides.

Today, scientists have found over 100 species of wild potatoes. Some are poisonous, but many are helpful in teaching us more about how plants survive.

Cracking the Potato Code

For a long time, scientists didn’t know exactly how potatoes came to be. They knew potatoes were related to tomatoes and Etuberosums, but they couldn’t figure out the family tree. That’s because different parts of the potato’s DNA told different stories. Some parts looked like tomato DNA, and others looked like Etuberosum DNA.

Finally, a team of scientists from around the world solved the puzzle. They studied over 400 plant genomes (complete sets of DNA), including rare wild potato species that grow in just one valley or mountaintop. Using computers and museum specimens, they created a genetic map. That map showed clearly: potatoes are the result of a lucky mix-up between the ancestors of tomatoes and Etuberosums.

A Lucky Time in History

This mix-up didn’t just happen randomly. It happened during a time when the Andes mountains were rising higher due to tectonic activity.

As the land changed, new types of environments appeared—high-altitude, cold, and dry places. These weren’t good for most plants, but the new potato hybrid had tubers that helped it survive.

Because potatoes could grow from pieces of themselves rather than from seeds, they quickly spread and adapted. They didn't need bees or wind to spread pollen. They didn’t even need perfect weather. Potatoes had a superpower: tubers.

The Potato Today—and Tomorrow

Thousands of years ago, people in South America began to farm potatoes. Today, the potato is one of the top four crops feeding the world, along with wheat, rice, and corn. Together, these crops provide about 80% of the calories that people eat.

But the potato still has secrets. For example, wild potatoes often carry special traits like resistance to insects, diseases, or dry weather. Scientists are studying these wild cousins to create better potatoes—ones that grow faster, survive drought, or resist new pests.

Right now, most farmers grow potatoes by cutting them into pieces and planting them. Each new plant is a clone of the old one.

This makes farming simple, but it also means all the potatoes are exactly the same. If a new disease appears, it can wipe them all out. That’s what happened during the Irish Potato Famine.

Scientists are now trying to use wild potato genes to breed stronger, more diverse potatoes. They’re even experimenting with growing potatoes from seeds instead of tubers, which could lead to faster-growing and safer crops.

A Delicious Coincidence

So, the next time you see a potato, think of it not just as a side dish but as the result of a 9-million-year-old accident—an ancient love story between two plants.

As one scientist put it, it’s kind of romantic. That bee carrying pollen back and forth had no idea it was helping create one of Earth’s most important foods.

And that, friends, is the incredible story of the potato—one of the most surprising and successful plants on the planet.

ancestor (n.): a plant, animal, or person that lived long ago and gave rise to later generations

climate (n.): the usual weather conditions in a particular place

clone (n.): a living thing that is an exact copy of another

diverse (adj.): showing a lot of variety; different from one another

environment (n.): the natural world or conditions where something lives

evolution (n.): the slow change of living things over time

gene (n.): a tiny part of a cell that carries information about traits

genetic (adj.): related to genes or inherited traits

habitat (n.): the natural home or environment of an animal or plant

hybrid (n.): a mix of two different kinds of plants or animals

important (adj.): having great value or meaning

nutrients (n.): substances that living things need to grow and stay healthy

pollen (n.): fine powder from flowers used to make seeds

reproduce (v.): to make more of the same kind

resistance (n.): the ability to fight off disease or problems

scientist (n.): a person who studies the natural world

species (n.): a group of living things that can breed and produce offspring

survive (v.): to stay alive

tuber (n.): a thick part of a plant that stores food and can grow into a new plant

vegetative (adj.): growing or spreading without seeds or flowers

► COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

— please answer with complete sentences

How many years ago did potato evolution start?

Did human beings engineer the evolution of the potato?

Where (on Earth) do potatoes come from?

What two plants are the “parents” of the potato?

What are tubers?

Why were tubers important to the survival and success of the potato?

Today, about how many species of potato are there?

How is the movement of tectonic plates and the evolution of the potato connected?

How do most farmers grow potatoes? (Hint: They do not plant potato seeds!)

Why might a new disease wipe all potatoes out?

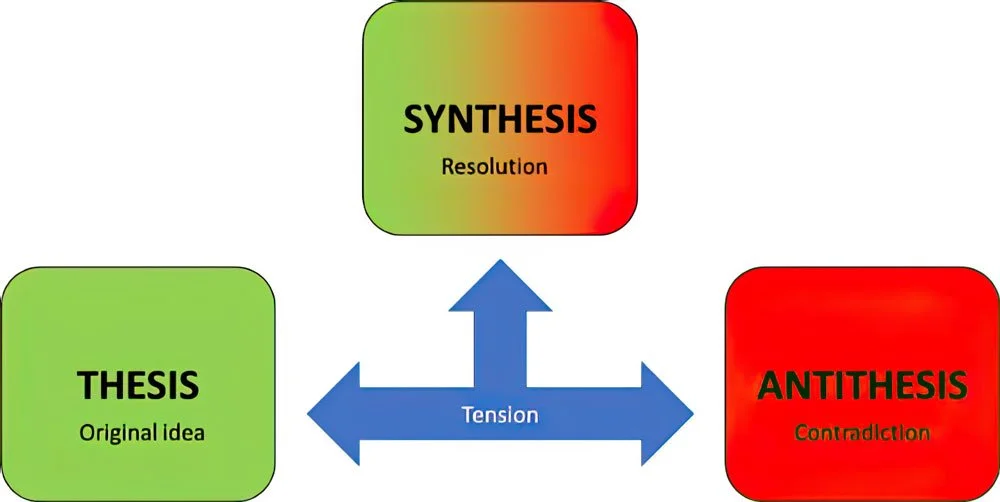

► From EITHER/OR ► BOTH/AND

► FROM Right/Wrong ► Creative Combination

THESIS — Argue the case that cloning potatoes is a brilliant way to grow potatoes.

ANT-THESIS — Argue the case that cloning potatoes is a risky way to grow potatoes.

SYN-THESIS — How might farmers and scientist combine these two perspectives?