THE INTELLIGENT OCTOPUS

• Read •

THE INTELLIGENT OCTOPUS

An Unlikely Comparison

What could octopuses possibly have in common with people?

They don’t have lungs or spines, and scientists can’t even agree on how to say the plural of their name! (Is it octopuses, octopi, or octopods?)

Still, octopuses can do some surprising things that remind us of ourselves. They can solve puzzles, learn by watching, and even use tools. These skills show real intelligence—and what’s most amazing is that the octopus’s brain works very differently from ours.

What Is an Octopus?

There are about 200 known species of octopuses.

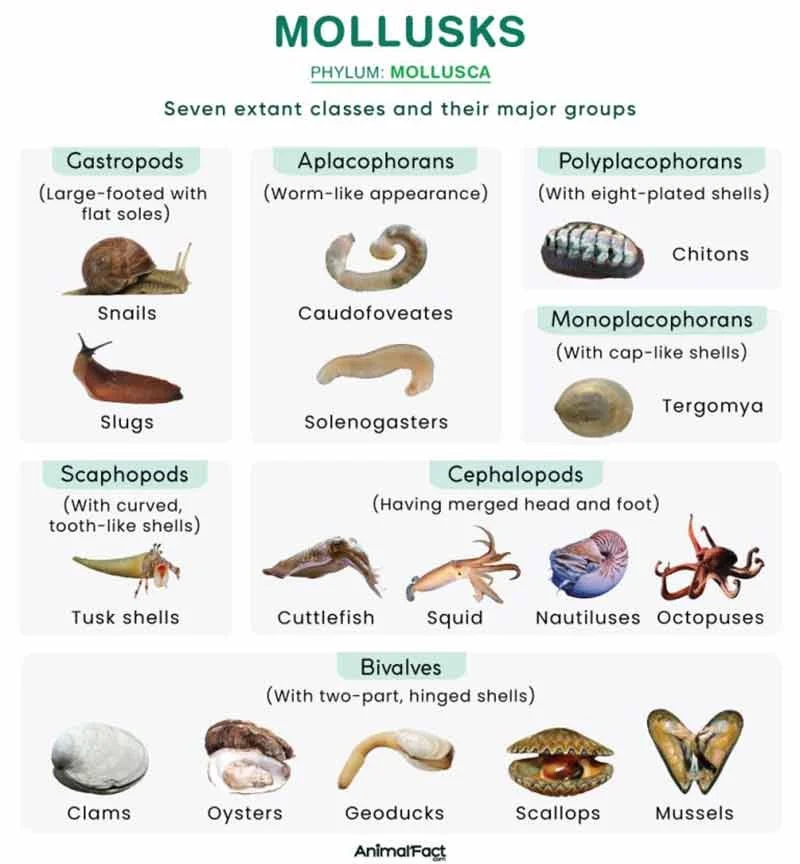

Octopuses are mollusks, a group of animals that also includes snails and clams.

Octopuses belong to a special group called Cephalopoda, which means “head-feet” in Greek. The name fits, since their arms are attached directly to their heads!

Inside that head is an impressive brain.

Compared to its body size, the octopus has one of the largest brains in the ocean. In fact, its brain-to-body ratio is similar to that of many intelligent animals, like dogs.

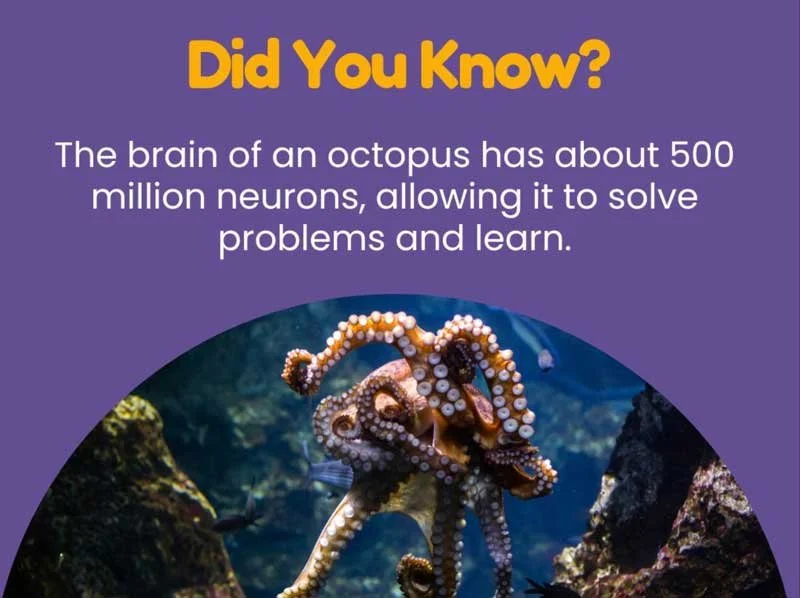

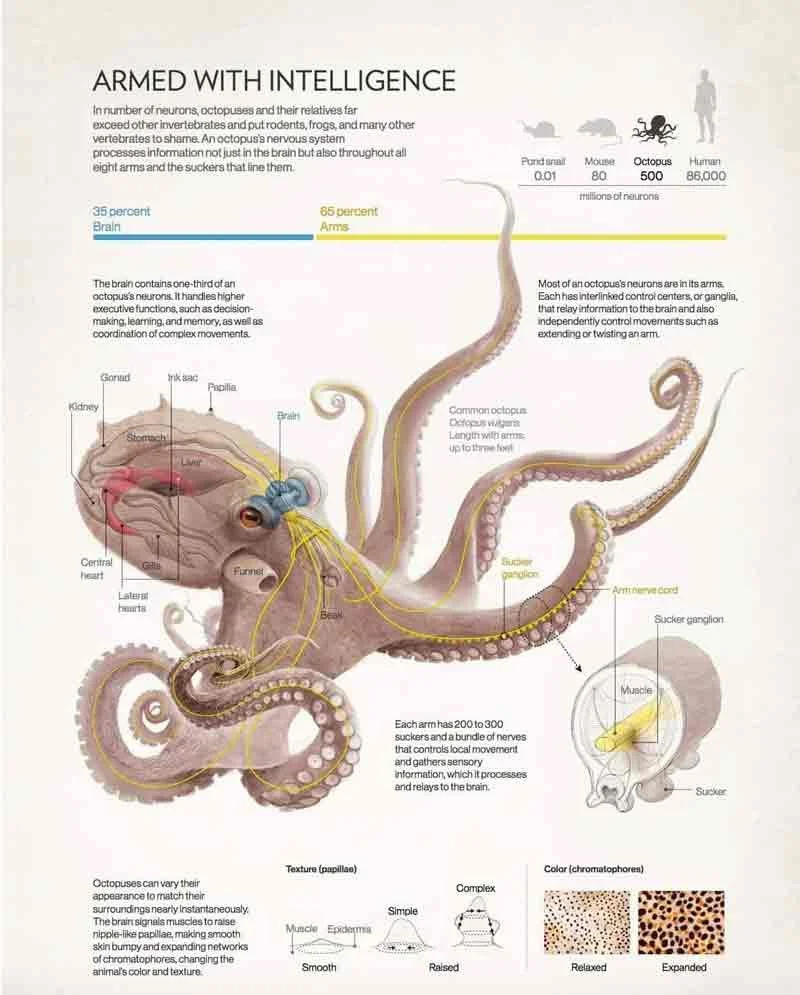

An octopus has about 500 million neurons—cells that carry messages through its nervous system. That’s roughly the same number of neurons as a dog!

But here’s where things get really interesting: most of those neurons aren’t in the brain at all.

A Brain Spread Through the Body

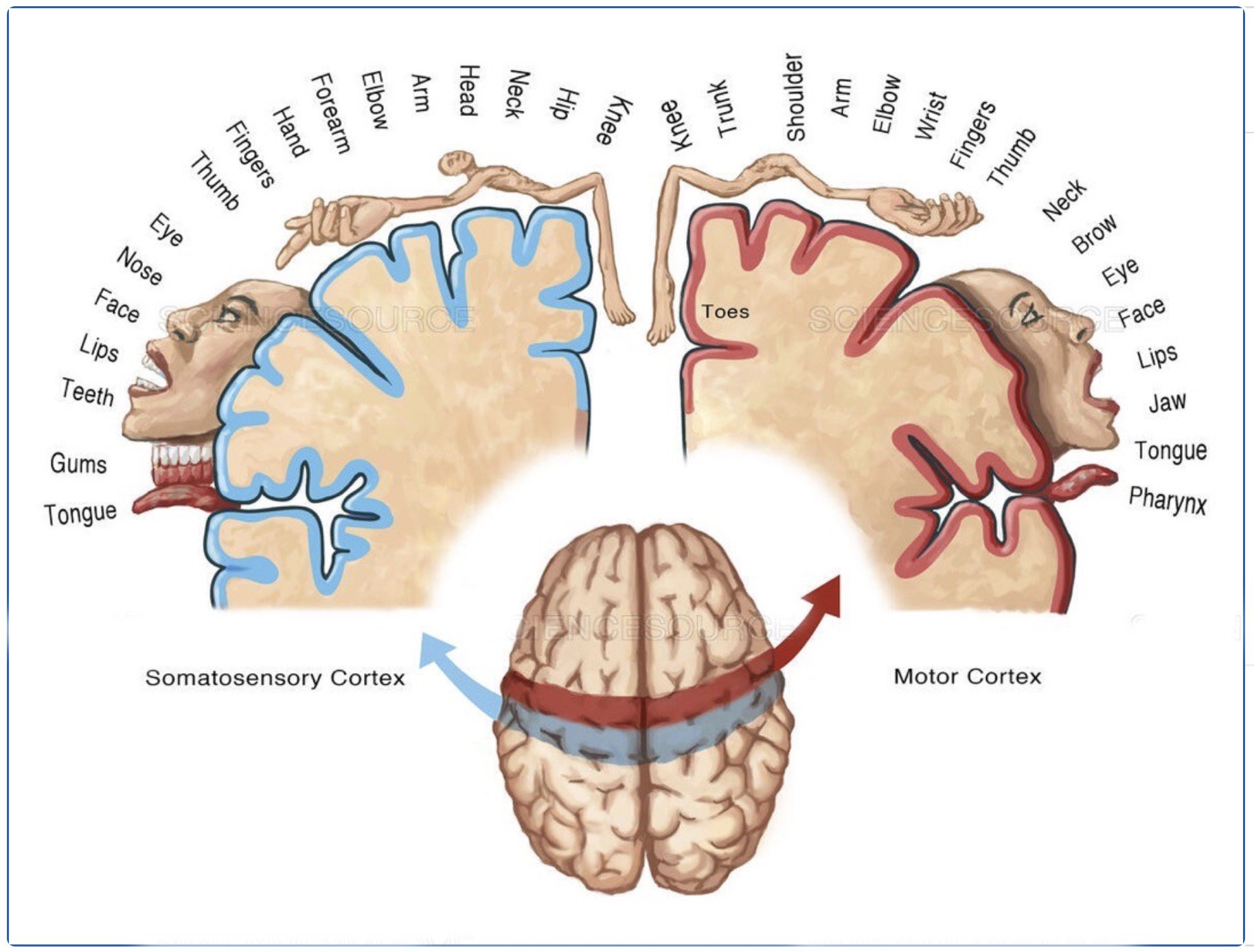

Humans and most other animals have a centralized brain that does almost all the thinking. The octopus, however, has a distributed nervous system.

Only about 10% of its neurons are in the brain itself. About 30% are in its two large optic lobes, which help it see and process visual information. The remaining 60% are found in its eight arms.

That means most of an octopus’s “thinking” happens in its arms!

Each arm can sense, react, and even make decisions on its own. It’s as if each arm has a tiny brain. For us, it would be like our arms being able to move and explore without needing instructions from our heads.

A Body with No Bones

Another reason octopuses are so unusual is that they have no bones—not even cartilage like a shark. Their soft, flexible bodies allow them to move in ways that are completely different from ours.

• Watch AFTER you’ve answered all 10 questions!

Humans and other animals with backbones have joints that only bend in certain directions. You can’t bend your elbow backward, for example.

But an octopus can bend its arms anywhere, in any direction, at any time. This gives it incredible freedom to twist, stretch, and squeeze through tight spaces.

Because of this flexibility, an octopus can shape its body into nearly endless positions. It can wrap its arms around objects, flatten itself to hide, or stretch out to look bigger and scarier to predators.

How an Octopus Moves and Eats

To understand how an octopus moves, imagine picking up an apple. Your brain sends signals to your arm muscles: reach out, open your hand, grab the apple, bend your elbow, and bring it to your mouth.

But an octopus doesn’t use a body map like we do.

• In human, our bodies are mapped onto our brains.

Instead, its brain stores behaviors rather than specific movements. When it sees food, it activates a “grab” behavior. That command travels through its nervous system to the arms.

Once the arms receive the message, they decide how to move. As one arm touches the food, a wave of muscle activity moves down the arm toward its base. Another signal travels from the base back toward the tip. When the two waves meet, the arm knows exactly where to bend and how to pull the food toward the mouth.

Each arm figures out its own movements while still working together with the others. This teamwork allows the octopus to move smoothly and respond quickly to whatever it touches.

Arms That Think

Because each arm can act independently, octopuses can solve problems in creative ways. Scientists have watched them open jars to reach food inside, escape from mazes, and explore new environments.

• Watch AFTER you’ve answered all 10 questions!

They can also camouflage themselves by changing both the color and texture of their skin to blend into rocks, coral, or sand. Some octopuses even mimic other sea creatures—like poisonous fish or sea snakes—to scare off predators.

This kind of intelligence shows that octopuses don’t just react to the world; they understand it and adapt to it. Each arm’s ability to “think” makes them some of the most flexible and inventive animals on Earth.

An Ancient Kind of Intelligence

Scientists believe cephalopods developed their complex brains long before most vertebrates (animals with backbones) did. That means the octopus’s kind of intelligence evolved on a totally separate path from ours.

This is one reason researchers find octopuses so fascinating: they show that intelligence can evolve in many different ways. By studying them, scientists can learn more about what intelligence and consciousness really mean—not just in humans, but in all living things.

Inspiring New Technology

Octopus intelligence has also inspired engineers and inventors. Because octopuses are soft and flexible, scientists are studying their movements to design soft robots—machines made of stretchy materials instead of metal.

These robots could move safely around humans or explore delicate environments like coral reefs.

By learning from octopuses, we might build machines that can squeeze through small spaces, adapt to new situations, and even “think” in flexible ways.

What We Can Learn from Them

The octopus reminds us that there’s more than one way to be smart. Its intelligence doesn’t come from a big central brain like ours but from a network spread throughout its body. Each arm contributes to the animal’s awareness, problem-solving, and ability to survive.

Who knows what other forms of intelligence might exist in our universe?

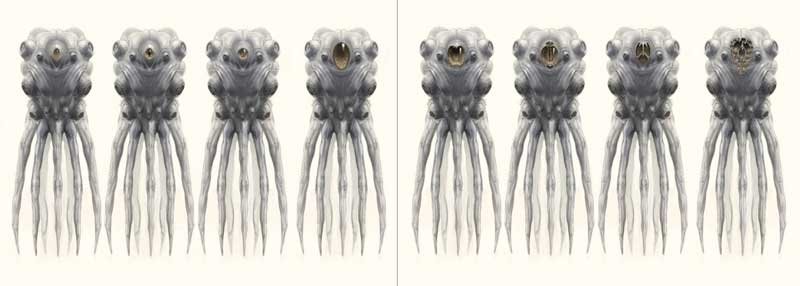

• Heptapod aliens from the movie “Arrival” (2016).

Studying the octopus helps us see that being smart isn’t about being human—it’s about being alive, aware, and able to adapt to the world around you.

Behavior – the way an animal acts or responds

Camouflage – the ability to blend into surroundings

Cephalopod – an ocean animal with a large head and arms, like an octopus or squid

Centralized – gathered in one main place

Consciousness – awareness or understanding of one’s surroundings

Distributed – spread out instead of being in one place

Evolve – to change and develop over a long period of time

Flexible – able to bend or change easily

Mollusk – a soft-bodied animal like a snail, clam, or octopus

Neuron – a cell that sends messages through the nervous system

Optic lobes – parts of the brain that control sight

Predator – an animal that hunts and eats other animals

Ratio – a comparison of two numbers or amounts

Tentacle – a flexible arm used for feeling and grabbing

Texture – how something feels to the touch

► COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

— please answer with complete sentences

What is the plural of octopus? Is there more than one correct plural?

What three skills show an octopus has real intelligence?

What group of animals does the octopus belong to?

Hint: Snails and clams belong to this group too.

About how many neurons (brain cells) does an octopus have?

What percentage of an octopus’s neurons are in its arms?

Note: Two possible answers: one in text, one in the diagram!

What can an octopus arm do that our arms cannot?

What can an octopus do that we cannot do because an octopus has no bones or cartilage? Give at least two examples.

As best you can, in a sentence or two describe the “teamwork” among an octopus’s eight arms.

Note: This is a difficult question; just do the best you can!

Why do researchers and scientists find octopuses so fascinating?

Think: What can we learn from studying octopuses?

If we based machines such as robots on an octopus design, what might that robot be able to do?

If you’re done with your 10 questions

and want to see just how amazing octopuses are,

take a look at “Octopus vs. Underwater Maze”!