Deep-Sea Mining:

A Risky Rush Beneath the Waves

And…

Name four metals deep-sea miners are looking for.

What are these metals used for?

Who decides what can (or cannot) happen on the deap-sea floor in international waters?

What does The Metals Company want to collect from the sea floor?

How much of the deep sea have we explored?

How is mining the ocean not like scooping sand at the beach?

If the deep-sea floor is damaged, how long does it take to repair itself?

How can the plumes of dust created by mining hurt sea creatures?

How much time before deep-sea mining starts do scientists want for research?

How might new technology change the “Mine! vs. Don’t Mine!” debate?

• Read •

Deep-Sea Mining:

A Risky Rush Beneath the Waves

Digging for Metals in the Ocean

Imagine digging for treasure at the bottom of the sea.

That’s what some companies and countries want to do — mine the deep ocean floor for metals like cobalt, manganese, nickel, and copper.

These metals are used to make things like electric cars, solar panels, and rechargeable batteries.

This idea has become more popular because people want cleaner energy and fewer fossil fuels.

But scientists and ocean experts are worried. They say we don’t know enough about how mining the deep sea might harm the ocean. And what we do know suggests the damage could last a very long time.

A Race for the Seafloor

Right now, most of the ocean floor is protected by international rules. A group called the International Seabed Authority, or ISA, decides what can and can’t happen in these deep-sea areas.

So far, they have allowed companies to explore the seafloor, but not to start mining.

But this might change soon. Some companies are now asking for the first-ever permits to begin actual mining in international waters.

The United States has taken steps to allow its companies to start mining faster, using a different set of rules.

This has caused a lot of debate.

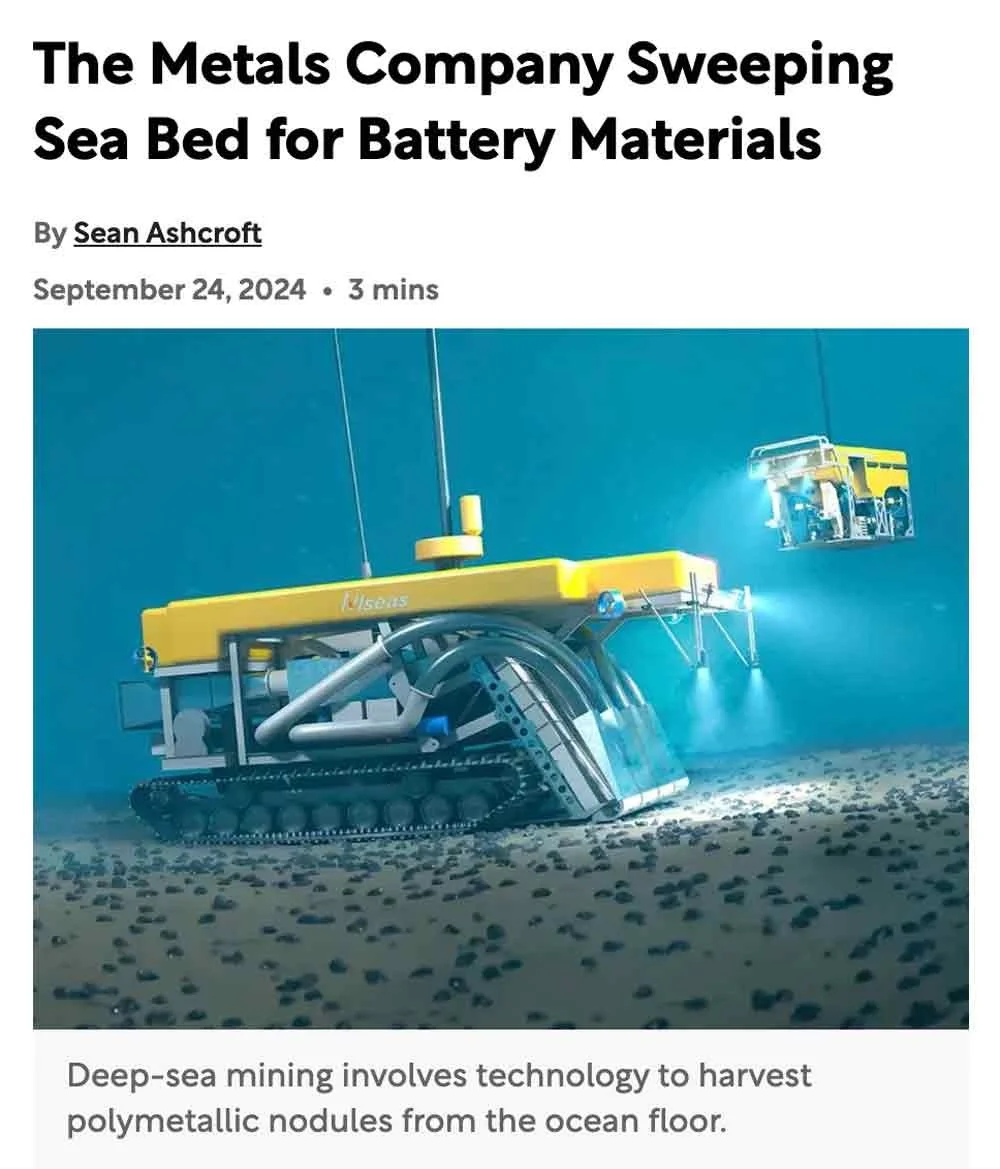

One company, The Metals Company, wants to collect rocks called polymetallic nodules. These are small lumps on the seafloor that contain useful metals.

The company says this is a way to get the metals we need without cutting down forests or digging up land. But others say deep-sea mining could cause serious harm to ocean life.

Life in the Deep Sea

The deep sea is full of mystery.

Most of it is thousands of feet below the surface, in cold, dark water. Very few people have ever seen it. In fact, scientists have only explored about 0.001% of it! That means we still don’t know about many of the creatures that live there.

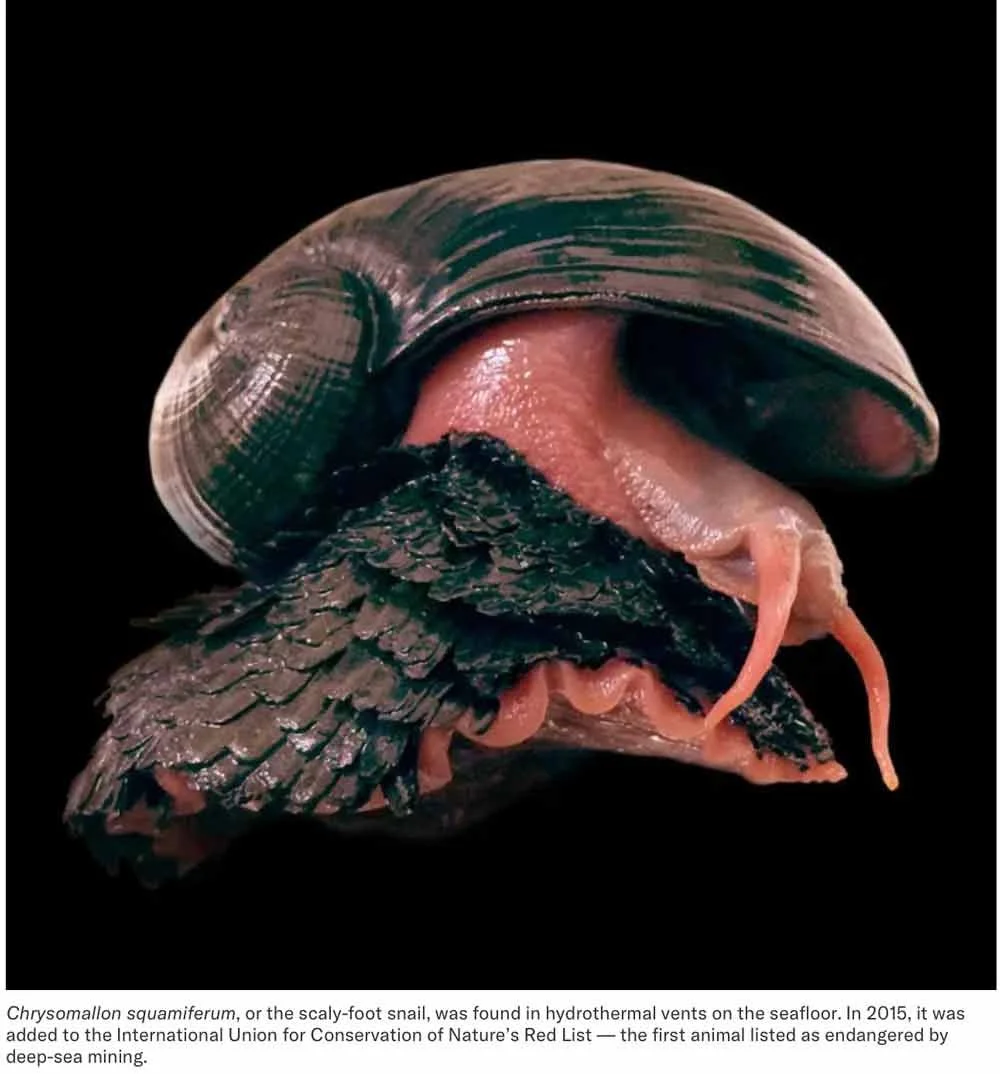

Some deep-sea animals have been discovered only recently.

One is the scaly-foot snail, which uses iron from hot underwater vents to build a strong shell. It is now listed as endangered because mining might destroy its home.

Another is a tiny crustacean called Macrostylis metallicola, which lives on the very nodules that companies want to collect. If we take away its home, it could disappear forever.

Scientists say there are probably many more deep-sea animals that haven’t even been discovered yet. If we mine before we learn about them, we could destroy them without even knowing they existed.

Lasting Damage

Mining the ocean is not like scooping sand at the beach.

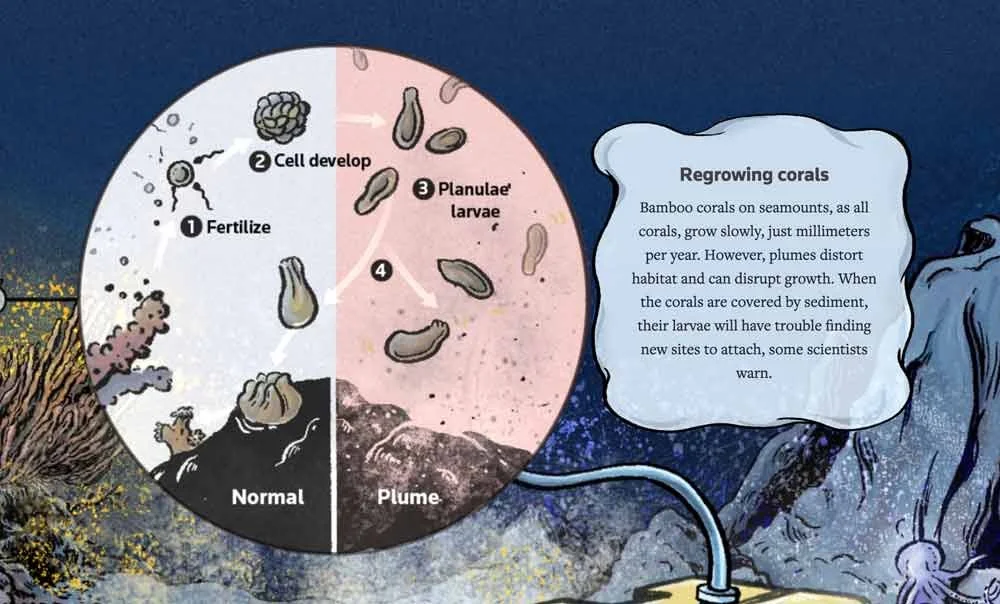

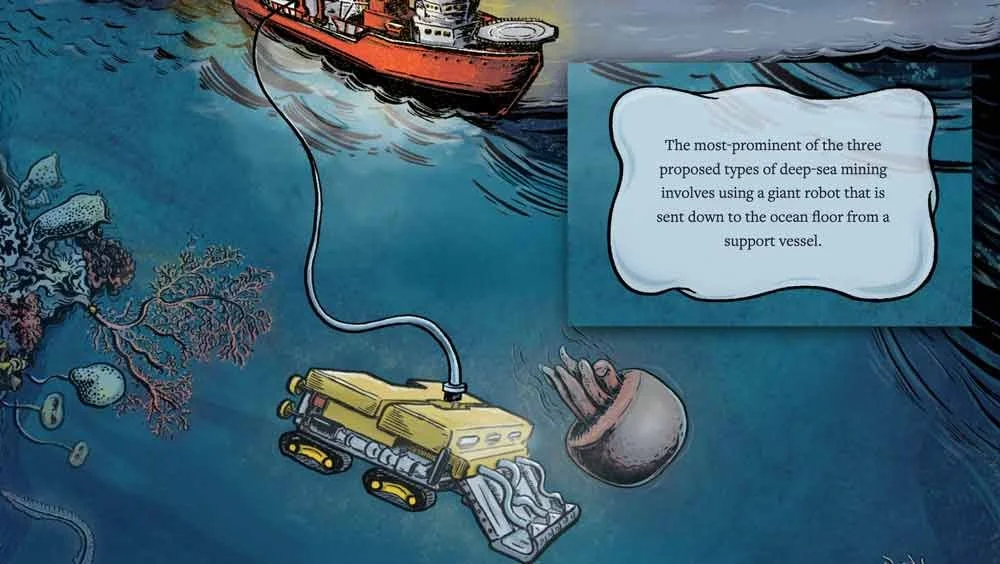

Machines would scrape the seafloor, kick up clouds of dirt, and possibly destroy fragile habitats.

Some deep-sea animals live on the bottom and don’t move much. They could be buried or hurt by the plumes of dust that mining creates.

In fact, one test was done back in 1979, when a machine was used to collect nodules from the Pacific Ocean floor.

When scientists returned to that site in 2023 — 44 years later — they found that the damage was still clearly visible. Some animals had returned, but the scars on the seafloor had not healed.

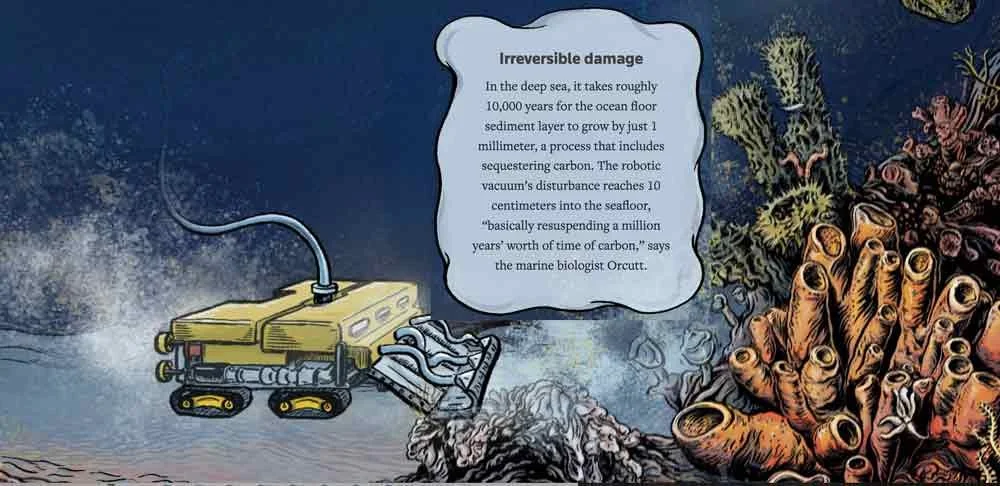

• Irreversible damage

There is also a worry that the mining dust might carry heavy metals into the ocean food chain, harming fish and other sea life.

We Need More Time

Because we know so little about the deep sea, many scientists are asking for a moratorium — a pause — on deep-sea mining.

They want more time to study the area and understand how mining would affect it. Some experts say we need at least 10 to 15 more years of research before any mining should begin.

And technology is changing fast.

The metals we’re rushing to collect may not be as important in the future. New types of batteries that don’t use cobalt or nickel are already being made. These batteries are cheaper, last longer, and may be better for the planet.

Different Views

Supporters of deep-sea mining say it could help stop climate change. If we get metals from the ocean, they say, we won’t need to damage forests and mountains on land.

But others argue that deep-sea mining is risky, expensive, and may not even be needed. They say that land-based mining is still easier and more affordable. And if the deep sea is damaged, it might never recover.

Some scientists say the deep sea is part of the common heritage of humankind, meaning it belongs to everyone — and we all share the responsibility to protect it.

What Happens Next?

The ISA is still deciding whether to allow deep-sea mining.

Meanwhile, ocean scientists and conservation groups are asking everyone to slow down and think carefully.

The ocean is huge, deep, and full of life we don’t fully understand.

Once we damage it, we may not be able to fix it.

That’s why many people believe we should protect it — at least until we know enough to make a wise decision.

Conservation (n.) – The protection of nature, animals, and the environment.

Crustacean (n.) – A type of animal with a hard shell, like crabs, shrimp, or some tiny sea creatures.

Damage (n./v.) – (n.) Harm that makes something less useful or broken; (v.) To cause harm or break something.

Endangered (adj.) – At risk of disappearing forever.

Environment (n.) – The natural world around us, including water, air, land, and living things.

Habitat (n.) – The natural home of an animal or plant.

International (adj.) – Involving more than one country.

Moratorium (n.) – A temporary stop or pause.

Nodule (n.) – A small lump or chunk found on the ocean floor that contains metal.

Pollution (n.) – Harmful things added to nature, like chemicals, trash, or smoke.

► COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

— please answer with complete sentences

Name four metals deep-sea miners are looking for.

What are these metals used for?

Who decides what can (or cannot) happen on the deap-sea floor in international waters?

What does The Metals Company want to collect from the sea floor?

How much of the deep sea have we explored?

How is mining the ocean not like scooping sand at the beach?

If the deep-sea floor is damaged, how long does it take to repair itself?

How can the plumes of dust created by mining hurt sea creatures?

How much time before deep-sea mining starts do scientists want for research?

How might new technology change the “Mine! vs. Don’t Mine!” debate?

► From EITHER/OR ► BOTH/AND

► FROM Right/Wrong ► Creative Combination

THESIS — Argue the case that we need deep-sea mining now to use fewer fossil fuels and help fight climate change.

ANT-THESIS — Argue the case that deep-sea mining is a bad idea and all deep-sea mining should be stopped now.

SYN-THESIS — Can you bring these two perspectives together?