On Being an Octopus

Nothing stretches our thinking about the mind

the way an octopus does

Why do scientists ask what it is like to be an octopus?

What “big” question did Thomas Nagel ask?

How do scientists imagine what an animal experiences?

What sense do bats use to “see” in the dark?

How many neurons does an octopus have?

Where are most of the octopus’s neurons located?

What did the maze experiment show about octopus arms?

Why might octopus experience be different from human experience?

What did experiments with chimpanzees teach us?

Why does learning about octopus minds matter?

Thinking with Eight Arms

When you imagine an octopus, you probably think about its eight arms and how it moves underwater. Octopuses are different from us in so many ways.

They have no bones, and their bodies can change shape. Scientists are fascinated by how an octopus’s mind works.

Reading about an octopus helps us imagine how a very different animal might think and feel.

The Big Question: What Is It Like?

A long time ago, a thinker named Thomas Nagel asked, “What is it like to be a bat?”

Nagel wondered how one being—like a bat—can truly understand what another being—like us—experiences.

Ours is not the only point of view on the planet. We share the world with many creatures.

An octopus is even more different from us than a bat because it evolved in a separate way and lives underwater with no bones at all. Asking what it is like to be an octopus pushes our minds to stretch beyond human experiences.

How Scientists Learn About Other Minds

Scientists study what animals do and how their bodies work to guess what they might experience.

For example, we humans imagine what it feels like to pinch our arm. We can use that idea to help imagine what an octopus might feel, too. We also need to learn about how an octopus’s nervous system is built, and how its arms and body work together.

Seeing with Sonar—Listening with Eyes

When bats fly, they use echoing sound to "see" their surroundings. They make clicking noises and listen to echoes to know where things are in the dark.

Humans don’t do that, but scientists say that using sonar feels kind of like seeing, even though it uses sound instead of light. When blind people learn to use clicking sounds to understand their surroundings, their brains actually begin to use vision areas to make sense of those clicks.

This shows us that different creatures might experience the world differently, even using different body parts.

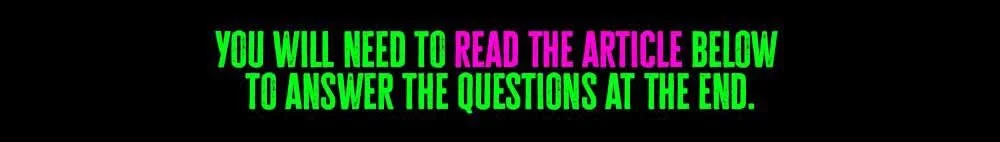

Octopus Brains and Taste in Their Arms

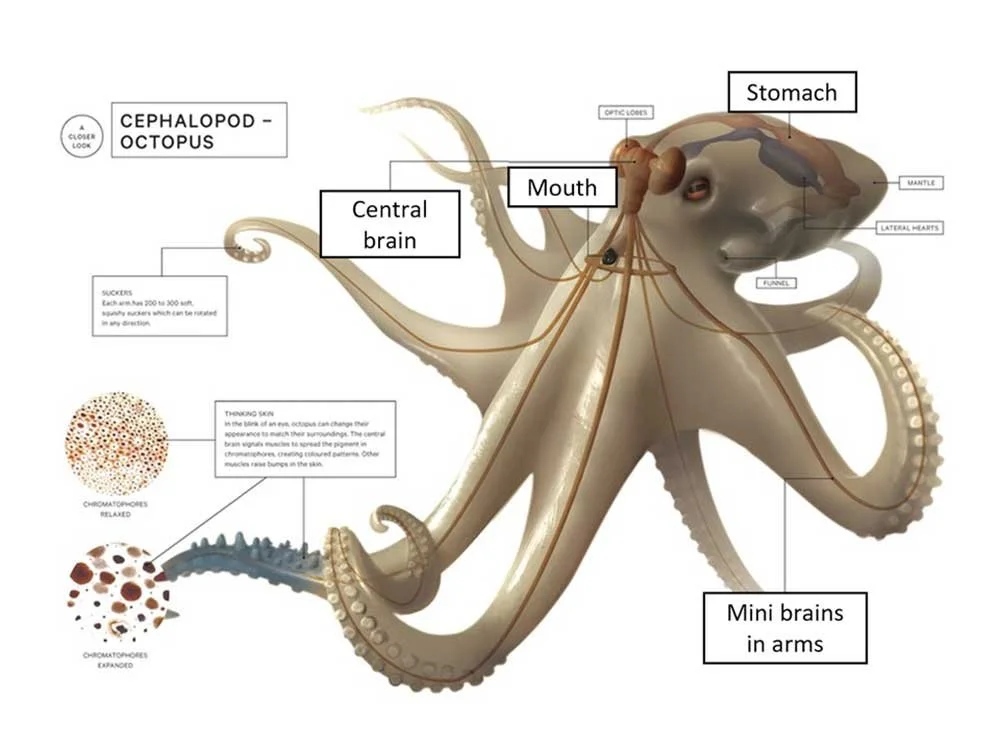

Octopuses are part of a group called mollusks.

Over a very long time—around 600 million years—octopuses evolved from simple sea creatures. They now have about 500 million neurons, which are brain cells. That’s not as many as people, but similar to a dog’s brain.

Most of those neurons are in their arms instead of in a central brain. This means their arms can act on their own, almost independently. An arm can move, feel, and explore while the main brain handles other tasks.

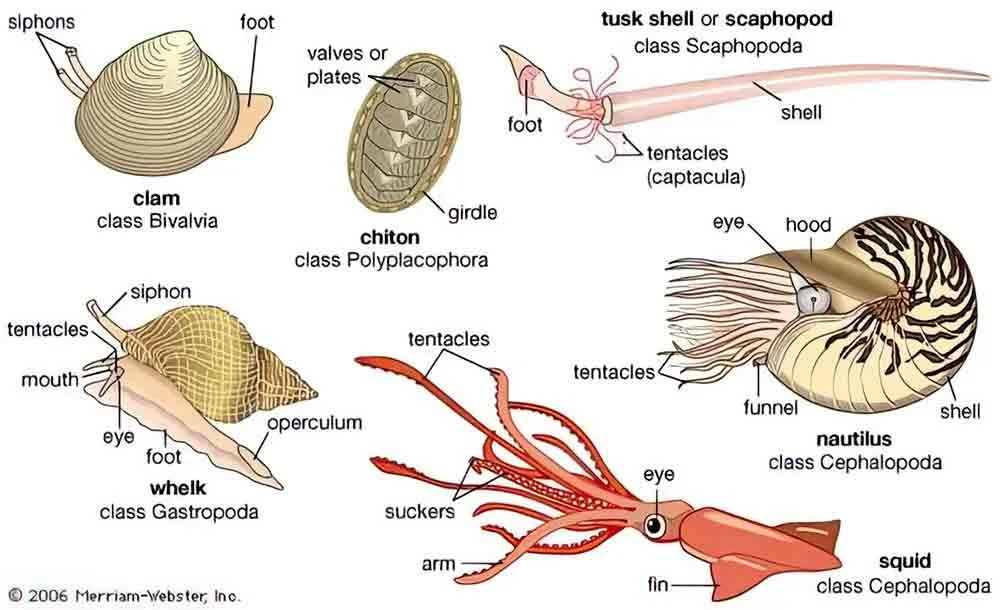

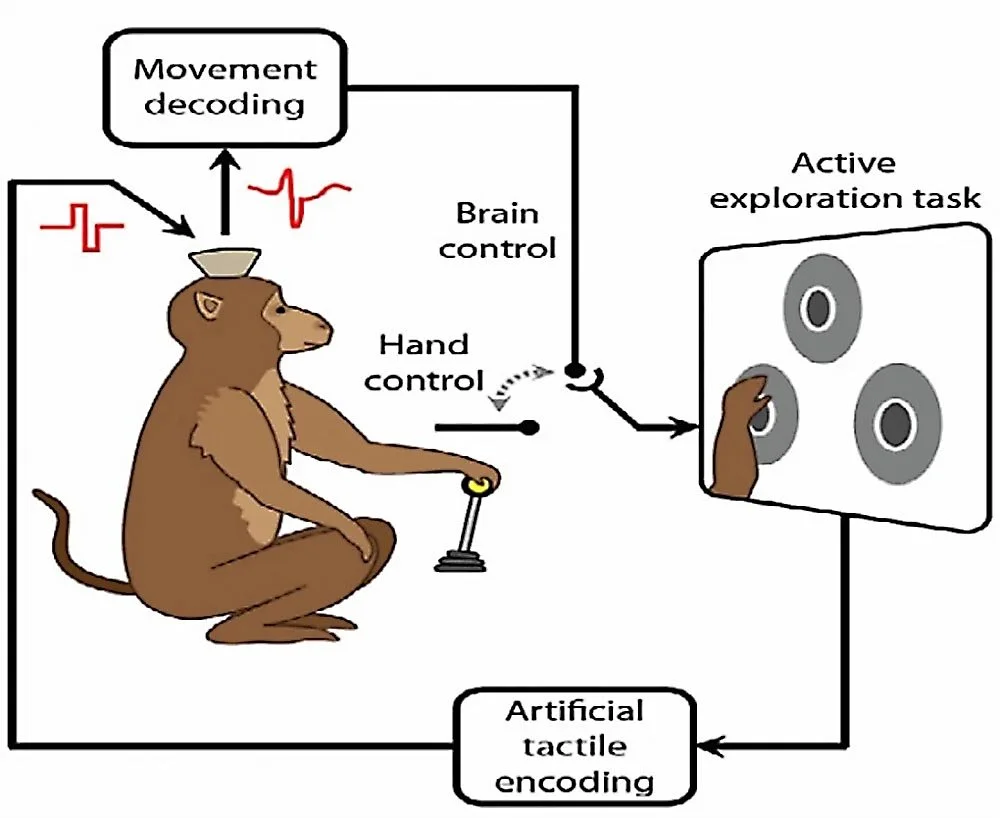

A Real-Life Experiment

Scientists set up a maze for octopus arms. They let only one arm climb out of water to reach hidden food. The octopus could see where the food was inside the maze, but the arm had to feel around too. The octopus learned to send its arm into the maze and find the food.

The experiment showed that octopuses use both seeing and feeling together. Their arms have their own control but still work with the brain’s instructions. It’s like their arms have a mind of their own but still need teamwork.

What Would It Feel Like?

When we reach out with our hand, we feel in two ways.

We feel the large movement, like moving our arm, and the small details, like the texture of something we touch.

An octopus does something similar. Its arms feel the big picture and also tiny details at the same time. But because part of the control happens in the arm itself and part in the brain, it may not feel exactly like it does for us.

The arm might act on its own as the octopus watches. It’s like raising your hand to scratch your head and noticing the exact spot it touches. Only with octopuses, the arm might move a little before the octopus even thinks about it.

Do Octopuses Know What They Do?

Some scientists wonder if animals know what they are doing. Do octopuses ever think, “That arm moved,” and know they made it happen?

Similar experiments were done with chimpanzees and monkeys. They moved something on a screen and then had to notice which object they moved. The chimpanzees could tell which object they controlled. That shows they knew the difference between what they did and what happened on its own.

Scientists wonder if octopuses could do the same if they were tested.

Why This Matters

Thinking about minds that are very different from ours helps us learn about minds in general.

We don’t need to believe that octopuses think exactly like humans, but we can use memory and imagination, plus facts about their brains and behaviors, to come closer.

Even though we cannot fully know what it is like to be an octopus, asking the question helps us appreciate other animal lives, and it helps science understand how diverse minds can be in nature.

Nervous system – The body’s network of nerves and brain cells that send messages.

Neuron – A nerve cell that sends signals in the brain and body.

Mollusk – A group of sea animals, including octopuses, clams, and snails.

Sonar – A way of finding things using sound waves.

Evolve – To change over a long time into a new form.

Centralized – Controlled from one main place, like a brain.

Distributed – Spread out, not controlled from one place.

Autonomous – Able to work by itself.

Agency – The ability to make choices and notice you are making them.

Philosopher – A person who explores big questions about life and thinking.

Behavior – What an animal does.

Converge – To come together in one place.

Peripheral – On the edge or outside part of something.

Analogous – Similar in some ways but not exactly the same.

Invertebrate – An animal with no backbone.

► COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

— please answer with complete sentences

Why do scientists ask what it is like to be an octopus?

What “big” question did Thomas Nagel ask?

How do scientists imagine what an animal experiences?

What sense do bats use to “see” in the dark?

How many neurons does an octopus have?

Where are most of the octopus’s neurons located?

What did the maze experiment show about octopus arms?

Why might octopus experience be different from human experience?

What did experiments with chimpanzees teach us?

Why does learning about octopus minds matter?

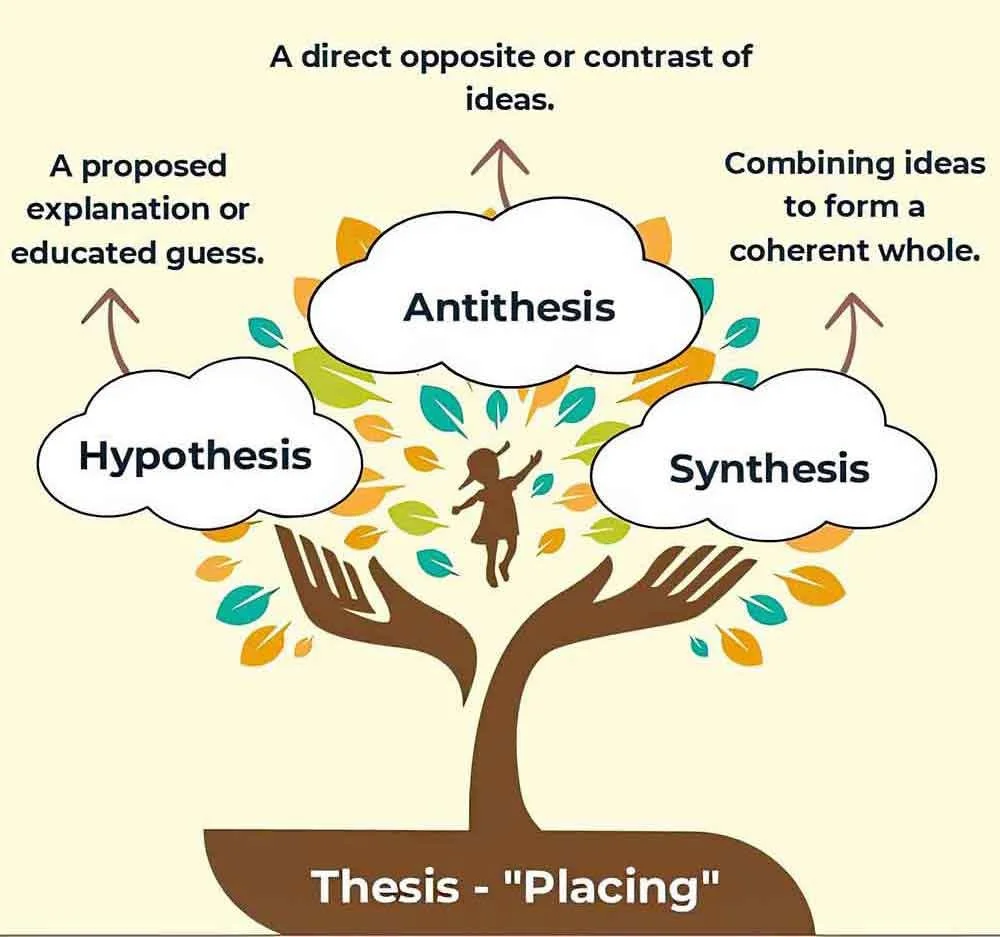

► From EITHER/OR ► BOTH/AND

► FROM Right/Wrong ► Creative Combination

THESIS — Argue the case that animal minds are so very different from human minds there’s no point in thinking about them.

ANT-THESIS — Argue the case that an animal’s mind is much like a human brain.

SYN-THESIS — How might the minds of humans and animals be both very much the same and very different?