How Megalodons Became Giant Hunters

What kind of animal was the megalodon?

How big was the megalodon?

What does being warm-blooded help animals do?

What problem did megalodons face by being warm-blooded?

What is “regional warm-bloodedness”?

What other shark lived at the same time and competed for food?

What is the full — species + genus — name for the megalodon?

Why did great white sharks survive while megalodons did not?

What do scientists think the megalodon’s high body temperature helped it do?

What question are scientists still trying to answer about megalodons?

A Shark That Ran Hot

Megalodons were some of the biggest meat-eating sharks that ever lived.

These giant sharks could grow up to 66 feet long—about as long as a school bus! Scientists now believe one of the secrets to the megalodon’s success was its warm body temperature.

By staying warmer than the water around it, the megalodon may have been able to swim faster and catch prey more easily. But this same trait may have also caused problems when food became hard to find.

Otodus megalodon

Megalodon’s full name is Otodus megalodon.

New studies on its teeth show that its body temperature was about 13 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than the surrounding seawater. That means it may have been at least partly warm-blooded.

This warm-bloodedness helped it move quickly and chase down other sea animals. As a result, the megalodon became one of the top hunters in the ocean.

Big Appetite, Big Trouble

Being warm-blooded can be helpful.

Animals that are warm-blooded, like mammals, can keep their bodies warm even when the outside temperature is cold. They can also be more active and faster than cold-blooded animals. But being warm-blooded also means an animal needs to eat a lot of food to keep its body running.

This was likely true for the megalodon. With such a large body and a fast-moving lifestyle, it needed to eat a lot. When food was easy to find, that wasn’t a problem. But when the oceans changed and food became harder to get, the megalodon may have been in trouble.

Robert Eagle, a scientist who studies ocean chemistry, explains that large animals with high metabolisms—meaning they burn a lot of energy—need lots of food to survive. If food runs out, those animals are more likely to die out. Eagle was part of the team that studied megalodon fossils to learn more about their body temperatures and how they lived.

Warm-Blooded Sharks

Most fish are cold-blooded, which means their body temperature changes with the water around them.

But some kinds of sharks can keep parts of their bodies warmer than the surrounding water. This is called "regional warm-bloodedness."

Modern sharks like great white sharks have this trait.

Scientists think the megalodon had it too. They think this helped it grow so large and become a top predator.

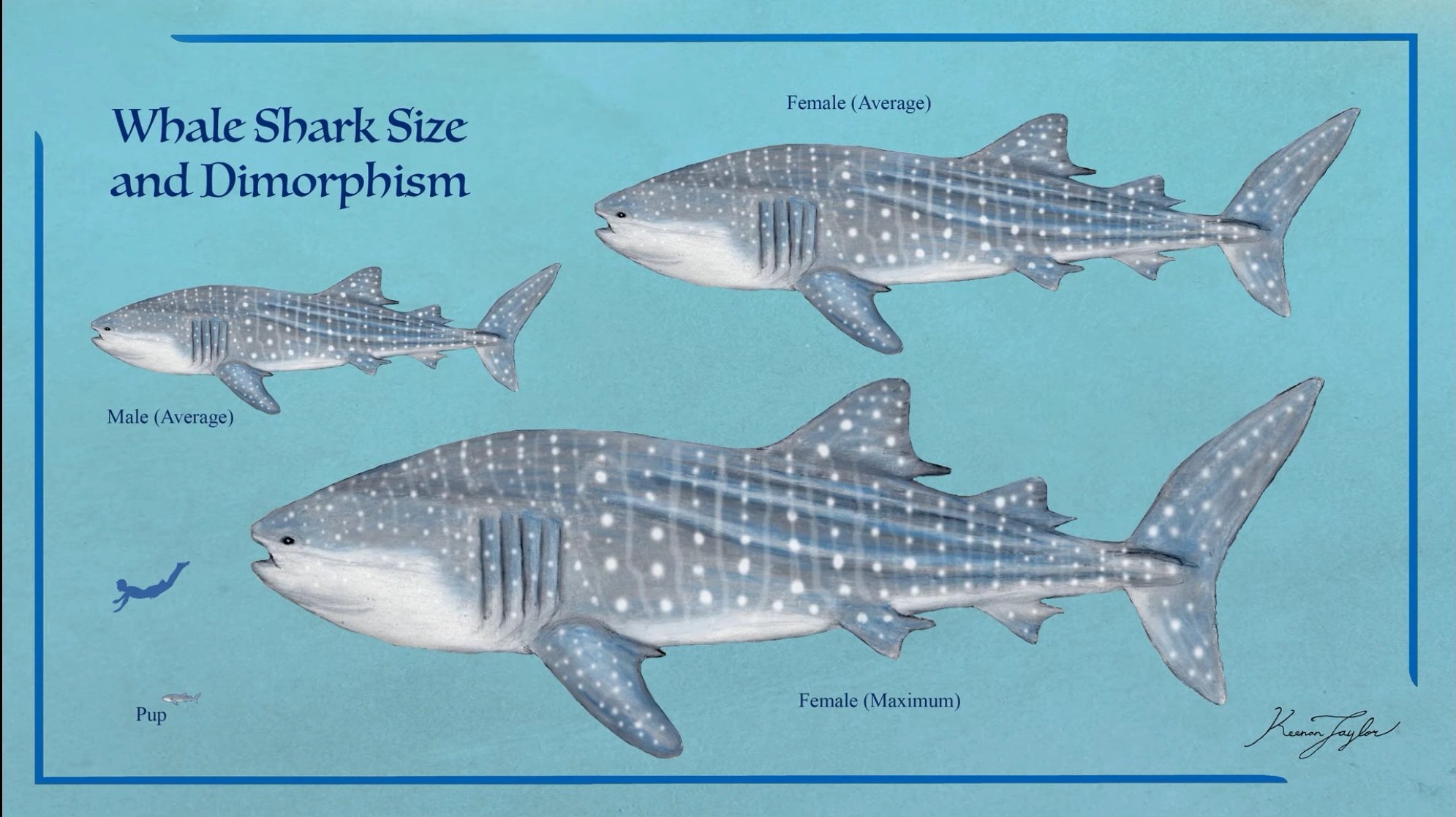

Some scientists also say that other big sharks, like whale sharks, became giants by using a different strategy. Whale sharks are filter feeders—they swim with their mouths open and eat tiny animals from the water.

Eagle says people have guessed for a long time that megalodons were warm-blooded in some way. Their huge size, fast swimming, and ability to live in both cold and warm waters suggest they could control their body temperature.

The Big Question

The big question is: how warm-blooded were they?

Eagle and his team wanted to compare the body temperatures of the megalodon to one of its main competitors: the great white shark. The megalodon lived from about 23 million to 2.6 million years ago.

Great white sharks appeared later, about 3.5 million years ago. That means they lived at the same time for a while and probably hunted the same types of prey.

During that time, the Earth’s climate was changing. The oceans cooled down, and many marine mammals—important food for both sharks—began to disappear.

Since megalodons needed so much food, this change may have been too much for them. Great white sharks, which were smaller and needed less food, survived.

Tooth Clues From the Past

Scientists don’t have megalodon bones, but they do have lots of megalodon teeth. These teeth are fossils, and they can tell us about the shark’s body temperature.

The enamel on the tooth holds special forms of carbon and oxygen. These are called isotopes. The way these elements bond together depends on temperature. So by looking closely at the isotopes, scientists can figure out how warm the shark’s body was.

Eagle and his team used this method on fossil teeth from megalodons, great white sharks, and cold-blooded sea creatures like mollusks that lived at the same time. The mollusks helped the scientists figure out what the ocean’s temperature was back then. Then, by comparing the sharks’ teeth to the mollusks’, they could see how much warmer the sharks’ bodies were.

The results showed that both great white sharks and megalodons were warm-blooded to some degree.

But megalodons had even higher body temperatures than great whites. Neither shark, though, was as warm as marine mammals like whales.

What Ended the Megalodon?

The warm body temperature gave megalodons a big advantage for millions of years.

They could swim far and fast, chase prey, and live in many kinds of waters. But when food became scarce, that same trait may have become a weakness. These huge sharks might have starved because they couldn’t find enough to eat.

Jack Cooper, a scientist who studies ancient animals, says the new study gives strong proof that megalodons were warm-blooded. He believes that their higher body temperatures helped them become top hunters, but also made it harder for them to survive when prey began to disappear.

NEW QUESTIONS

Now Eagle and his team are working on another question: did the megalodon become warm-blooded first, or did it become a top predator first? They want to learn more about how body temperature and hunting style worked together in the shark’s evolution.

In the end, the story of the megalodon is not just about how big it was, but how the way it lived may have led to its fall. Scientists hope to learn more by continuing to study these fascinating animals from the past.

Megalodon – A huge, extinct shark that lived millions of years ago.

Fossil – Remains or imprints of ancient animals or plants.

Prey – An animal that is hunted and eaten by another animal.

Metabolism – The process your body uses to get energy from food.

Endothermy – Another word for warm-bloodedness.

Extinct – A species that no longer exists.

Isotope – A form of a chemical element that can help scientists study the past.

Marine mammal – An animal that lives in the sea and breathes air, like whales and dolphins.

Apex predator – A predator at the top of the food chain, with no natural enemies.

Evolution – The slow change of animals or plants over a very long time.

► COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

— please answer with complete sentences

What kind of animal was the megalodon?

How big was the megalodon?

What does being warm-blooded help animals do?

What problem did megalodons face by being warm-blooded?

What is “regional warm-bloodedness”?

What other shark lived at the same time and competed for food?

What is the full — species + genus — name for the megalodon?

Why did great white sharks survive while megalodons did not?

What do scientists think the megalodon’s high body temperature helped it do?

What question are scientists still trying to answer about megalodons?

► From EITHER/OR ► BOTH/AND

► FROM Right/Wrong ► Creative Combination

THESIS — Argue the case that it’s better to be a warm-blooded animal than a cold-blooded animal.

ANT-THESIS — Argue the case that it’s better to be a cold-blooded animal than a warm-blooded animal.

SYN-THESIS — Can both be true? Explain.