THE PHYSICS OF TSUNAMIS

When do tsunami become dangerous?

What causes most tsunamis?

Where might we find tectonic plates?

Sometimes one tectonic plate slides beneath another tectonic plate. What is this process called?

Tsunamis can be caused by underwater earthquakes. Name three other ways tsunamis might be formed. (Hint: look at one of the diagrams!)

Note at least two things that happens when a tsunami wave comes to shallow water.

If you were on a beach, what is one warning sign that a tsunami might be coming?

If you know a tsunami is coming, what should you do?

In 2004, an enormous earthquake struck near what island in Indonesia?

How do scientists know a tsunami has been created and is racing at 500mph across the ocean?

• Read •

THE PHYSICS OF TSUNAMIS

What Is a Tsunami?

A tsunami is a giant ocean wave caused by sudden movement under the sea. These waves can travel across the ocean at amazing speeds. At first, they might not look dangerous. Out in the open ocean, a tsunami wave can be almost invisible.

But when it gets close to land, it becomes much larger—and much more dangerous.

How Tsunamis Form

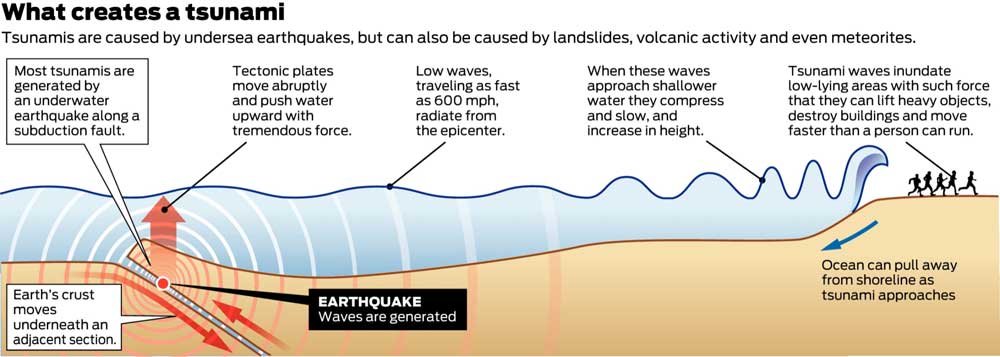

Most tsunamis are caused by underwater earthquakes. Earth’s outer layer, called the crust, is made of huge pieces called tectonic plates.

These plates move very slowly. Sometimes, two plates push against each other. One plate may slide under the other. This is called subduction.

When this happens, energy builds up over time. At some point, the energy becomes too much. Suddenly, the plates move, and the energy is released.

This causes the seafloor to rise or fall. When a large area of the ocean floor shifts like this, it pushes the water above it. That push creates a tsunami wave.

Other Causes of Tsunamis

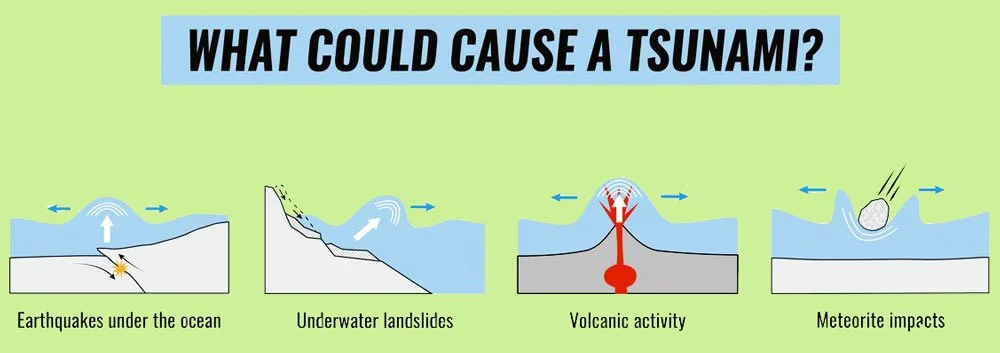

Although earthquakes are the main cause of tsunamis, they are not the only one. Underwater volcanic eruptions can also create tsunamis.

So can landslides that happen underwater or near the coast. Even something very large falling into the ocean—like a meteorite—can create a tsunami. These events are rare, but they show that there is more than one way a tsunami can begin.

What Happens to a Tsunami Near Shore

A tsunami wave travels fast in deep ocean water—up to 500 miles per hour—but the wave is low and hard to notice.

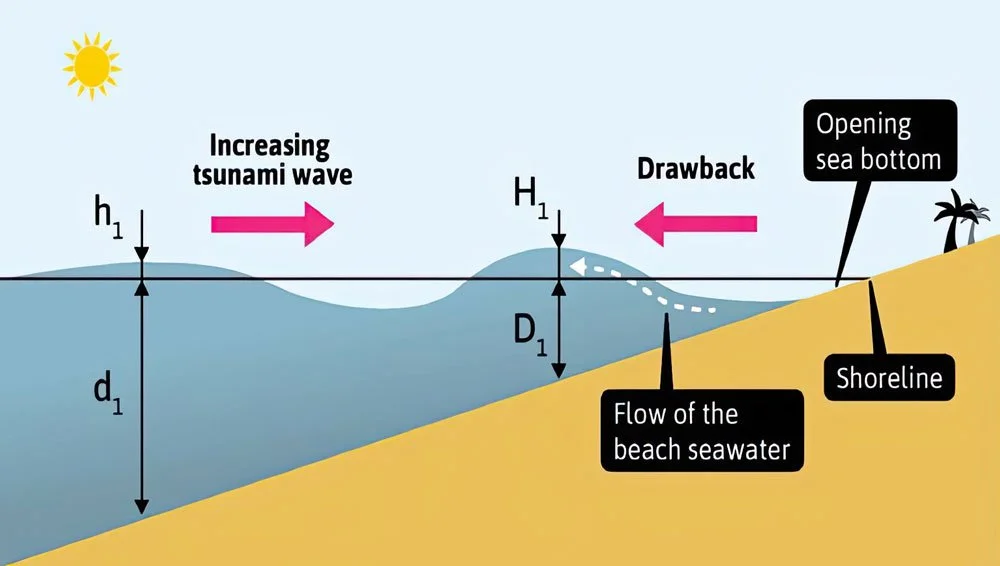

As it nears the shore, the water becomes shallower. This slows down the wave. The wave also changes shape. Its energy gets squeezed upward, and it becomes much taller.

This process is called wave shoaling.

As the wave rises, it becomes very powerful. When it crashes onto land, it can flood towns, break buildings, and sweep people and things away.

Warning Signs of a Tsunami

One warning sign of a tsunami is when the ocean suddenly pulls back, and the shoreline moves out farther than usual. This might mean that the first part of the wave is a trough—the bottom part of the wave. If you ever see this, it’s important to move to higher ground immediately.

But not all tsunamis begin this way. Sometimes, the tallest part of the wave comes first, without any warning at all.

The 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami

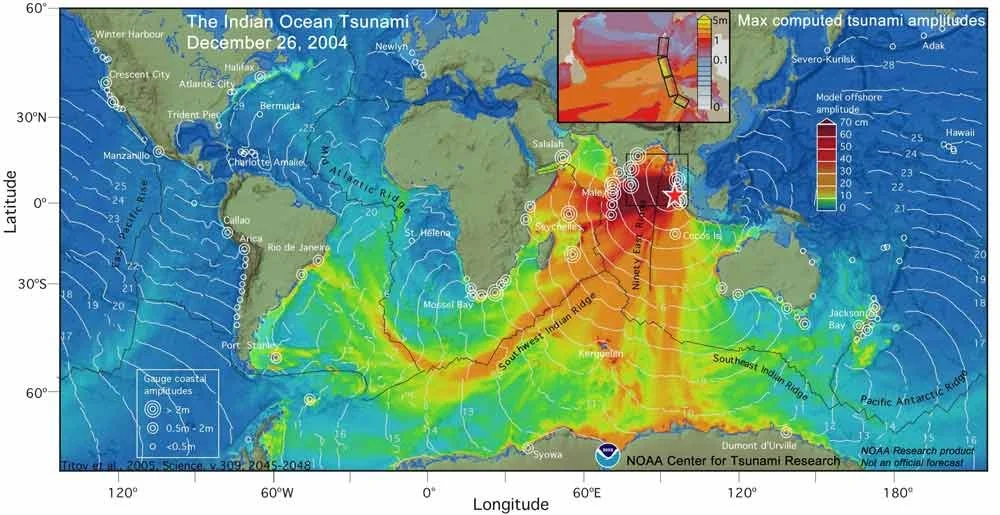

One of the deadliest tsunamis in history happened in 2004. An enormous earthquake struck near Sumatra, an island in Indonesia.

The quake was very powerful—measuring between 9.1 and 9.3. It lasted almost 10 minutes and caused the ocean floor to rise suddenly. This pushed up a huge amount of water and started a massive tsunami.

Waves over 30 meters (nearly 100 feet) tall crashed into nearby coasts.

The tsunami moved across the ocean at high speeds. It reached nearby countries like Thailand within hours, and even hit parts of Africa.

More than 340,000 people lost their lives. Over 100,000 people died in Sumatra alone.

At the time, there was no early warning system in the Indian Ocean. People didn’t know the wave was coming, and there was no time to escape.

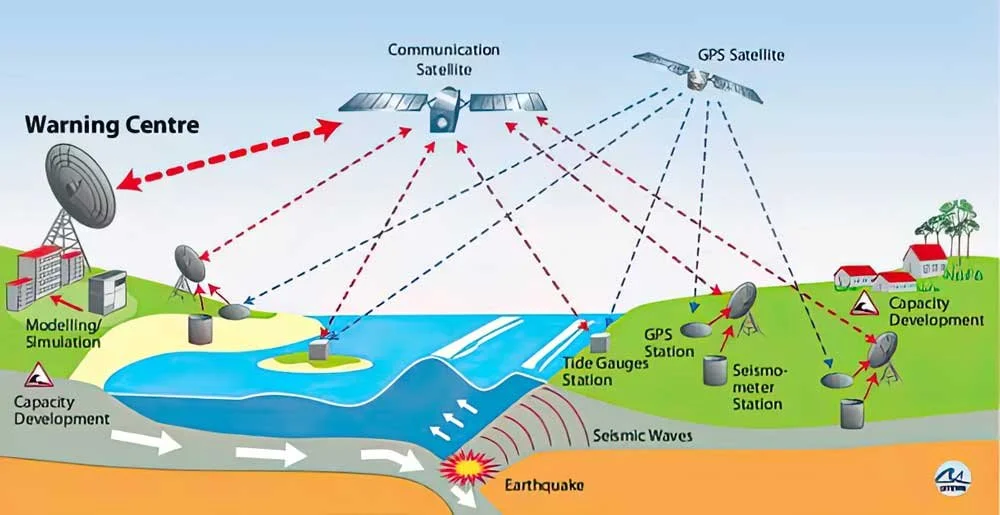

Building Better Warning Systems

After the 2004 tsunami, countries around the world took action. Scientists placed special buoys and pressure sensors in the ocean.

These tools help detect sudden changes in sea level. If a tsunami starts, the sensors send signals to satellites, which alert warning centers on land. This gives people time to evacuate and get to safety.

Even a few minutes’ warning can save thousands of lives. In some places, like Japan and the United States, these systems are already in place. But not all countries have the same technology or warning systems.

Can We Stop a Tsunami?

We can’t stop a tsunami, but we can try to reduce its damage. In Japan, after a major tsunami in 2011, the country built a huge seawall to protect its coast.

It’s 400 kilometers long and up to 15 meters tall in some places. Before 2011, Japan had shorter seawalls, but they were not strong enough. The 2011 tsunami was larger than expected and washed over them.

Even with early warning systems, tsunamis can still surprise people. Sometimes, experts can’t predict exactly how tall a wave will be. That’s why it’s important to be prepared, especially in areas where tsunamis are more common.

Why Tsunamis Matter

Tsunamis are powerful and dangerous, but they also teach us about how our planet works.

By learning about plate movement, ocean waves, and warning systems, we can better protect people around the world. Knowing the signs of a tsunami—and having good tools to detect them—can make the difference between life and death.

amplitude (n.) – the height of a wave from its middle to the top or bottom

buoy (n.) – a floating object that measures or marks something in the ocean

crust (n.) – the outermost layer of the Earth

energy (n.) – power that causes things to move or change

epicenter (n.) – the point on Earth’s surface directly above where an earthquake starts

evacuate (v.) – to leave a place quickly for safety

landslide (n.) – when a large amount of earth, rock, or mud slides down a slope

magnitude (n.) – the size or strength of something, like an earthquake

meteorite (n.) – a rock from space that hits Earth

plate (n.) – a large, flat piece of Earth's outer shell that moves slowly

pressure (n.) – the force of one thing pressing on another

recede (v.) – to move back or away from a place

sensor (n.) – a device that detects or measures something

seawall (n.) – a wall built along the coast to block ocean waves

shoaling (n.) – the process of a wave getting taller as it moves into shallow water

subduction (n.) – when one tectonic plate slides under another

tectonic (adj.) – related to the large plates that make up Earth’s surface

trough (n.) – the lowest part of a wave

► COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

— please answer with complete sentences

When do tsunami become dangerous?

What causes most tsunami?

Where might we find tectonic plates?

Sometimes one tectonic plate slides beneath another tectonic plate. What is this process called?

Tsunamis can be caused by underwater earthquakes. Name three other ways tsunamis might be formed. (Hint: look at one of the diagrams!)

Note at least two things that happens when a tsunami wave comes to shallow water.

If you were on a beach, what is one warning sign that a tsunami might be coming?

If you know a tsunami is coming, what should you do?

In 2004, an enormous earthquake struck near what island in Indonesia?

How do scientists know a tsunami has been created and is racing at 500mph across the ocean?

► From EITHER/OR ► BOTH/AND

► FROM Right/Wrong ► Creative Combination

THESIS — Argue the case that we should never build in low-lying areas that might be struck by a tsunami. (Honolulu is built in a low-lying area that could be hit by a tsunami.)

ANT-THESIS — Argue the case that we can — and need to — build in low-lying areas that could be in danger from a tsunami.

SYN-THESIS — How might these two perspectives be brought together?