DEMOCRACY IN ANCIENT GREECE

What is a lottery?

If elections weren’t a big part of democracy in ancient Athens, who served in government?

What kind of democracy they they have in ancient (500 BCE) Athens?

What did the ancient Athenians call their 500-member governing council?

What’s the process of random selection called? (Hint: fancy word ending in -tion.)

What became the duty of all citizens?

Who was left out of Athenian "rule by the many"?

What percentage of the population was eligible to participate in government?

Who criticized this kind of democracy as chaotic and foolish? (Hint: He’s a very famous philosopher.)

What problem do many people see in democracy today?

• Read •

DEMOCRACY IN ANCIENT GREECE

Hey, congratulations!

You've just won the lottery!

• You won!

Only the prize isn't cash or a luxury cruise. It's a position in your country's national legislature. And you aren't the only lucky winner. All of your fellow lawmakers were chosen in the same way.

This might strike you as a strange way to run a government—let alone a democracy. Elections are the epitome of democracy, right?

Well, the ancient Athenians who coined the word had another view. In fact, elections only played a small role in Athenian democracy.

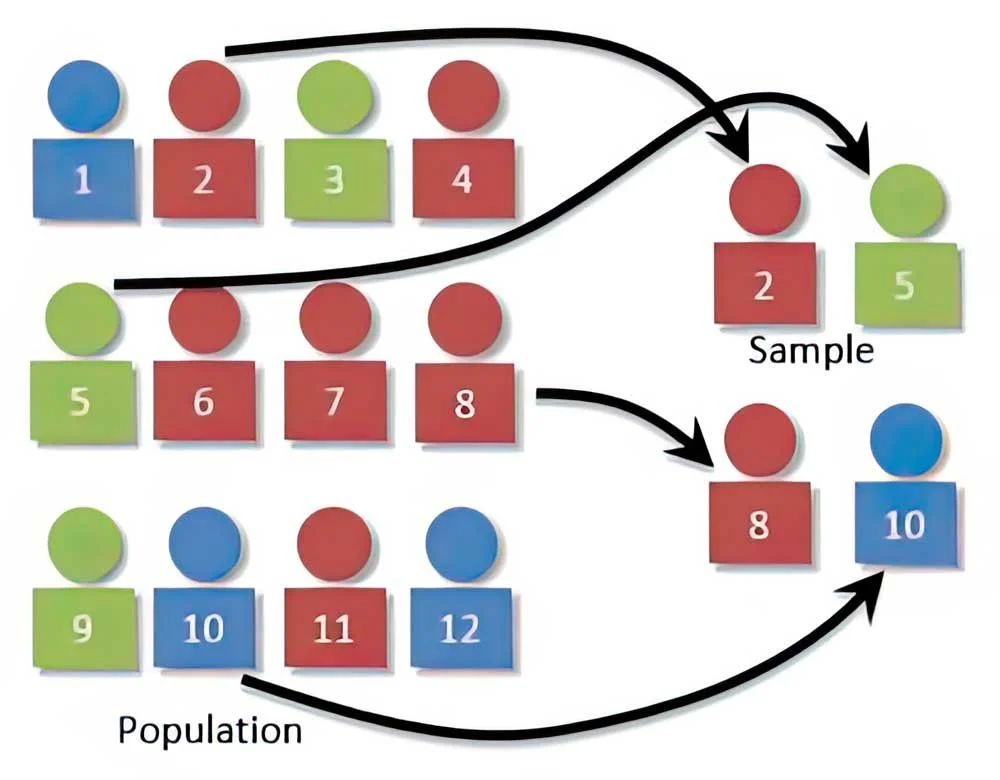

Most offices were filled by random lottery from a pool of citizen volunteers.

• Ramdom sampling is used in scientific research.

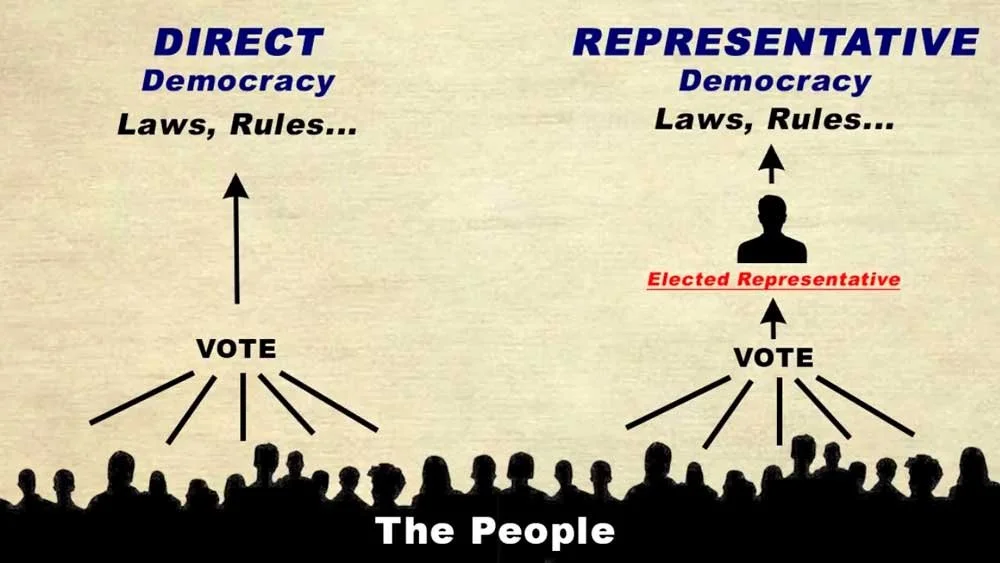

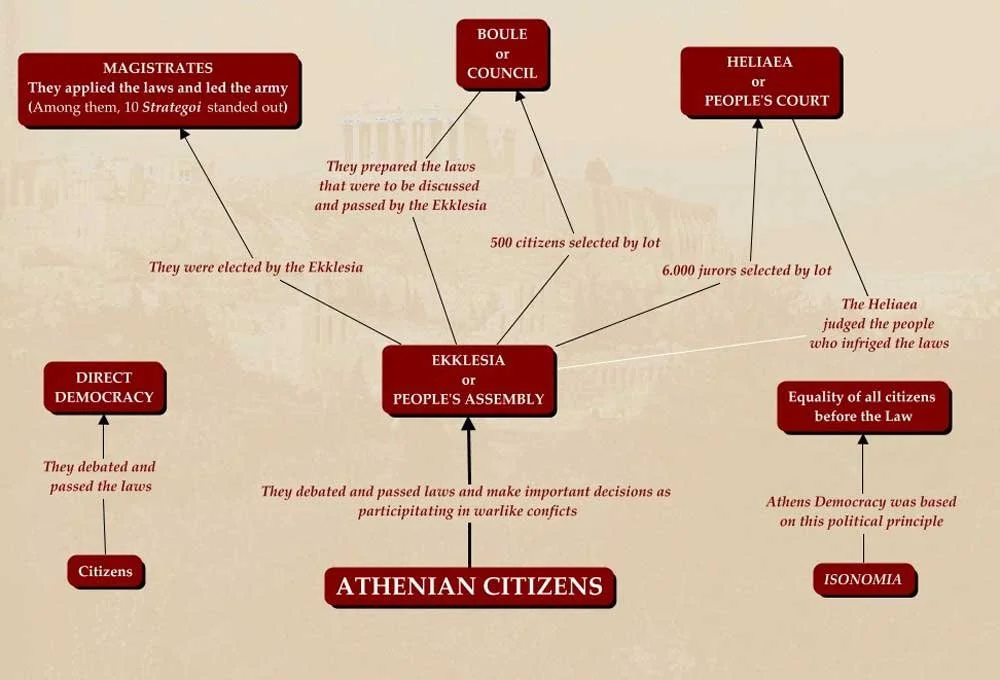

Unlike the representative democracies common today—where voters elect leaders to make laws and decisions on their behalf—5th-century BCE Athens was a direct democracy.

It encouraged wide participation through the principle of ho boulomenos, or "anyone who wishes."

This meant that any of its approximately 30,000 eligible citizens could attend the ecclesia, a general assembly that met several times a month.

In principle, any of the 6,000 or so who showed up at each session had the right to address their fellow citizens, propose a law, or bring a public lawsuit.

Of course, a crowd of 6,000 people all trying to speak at the same time wouldn't have made for effective government.

So the Athenian system also relied on a 500-member governing council called the Boule.

• The BOULE is top center.

This boule set the agenda and evaluated proposals.

There were also hundreds of jurors and magistrates to handle legal matters.

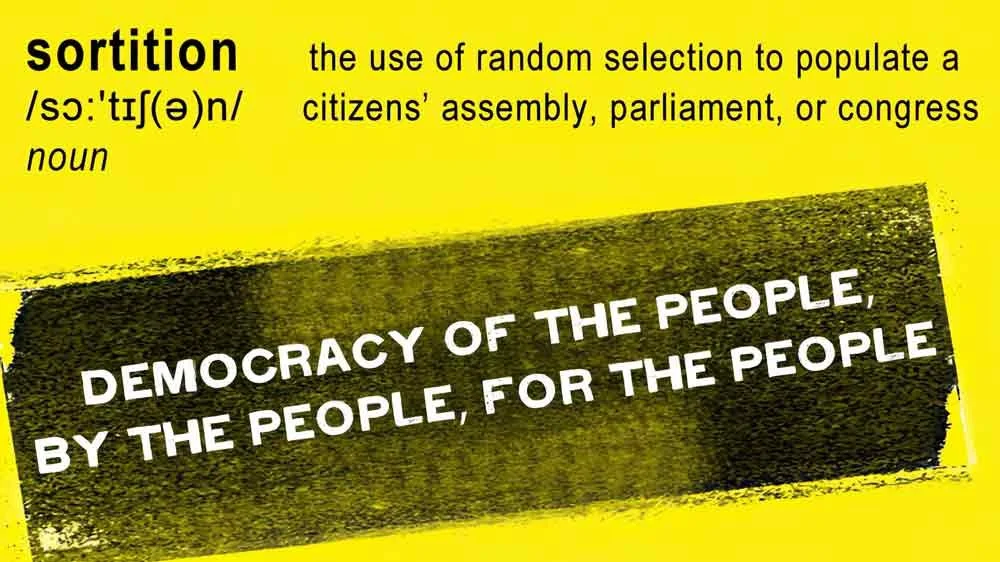

Rather than being elected or appointed, the people in these positions were chosen by lot. This process of random selection is known as sortition.

The only positions filled by elections were those seen as requiring special expertise—such as generals. But these jobs were considered aristocratic (rule by the best), as opposed to democratic (rule by the many).

How did this unusual system come to be?

Well, democracy arose in Athens after long periods of social and political tension marked by conflict among nobles.

Powers that had once been restricted to elites—like speaking in the assembly or voting—were expanded to ordinary citizens.

The ability of regular people to do these tasks well became a key part of Athens’ democratic beliefs.

Rather than being a privilege, civic participation became the duty of all citizens. Sortition and strict term limits helped prevent the rise of ruling classes or political parties.

rule by the many

But by 21st-century standards, Athenian "rule by the many" left out a lot of people.

Women, slaves, and foreigners were not given full citizenship. And if we filter out those too young to serve, only 10–20% of the population was eligible to participate in government.

Some ancient thinkers, like Plato, criticized this kind of democracy as chaotic and foolish.

• Plato was a famous philosopher, a student of Socrates and teacher of Aristotle.

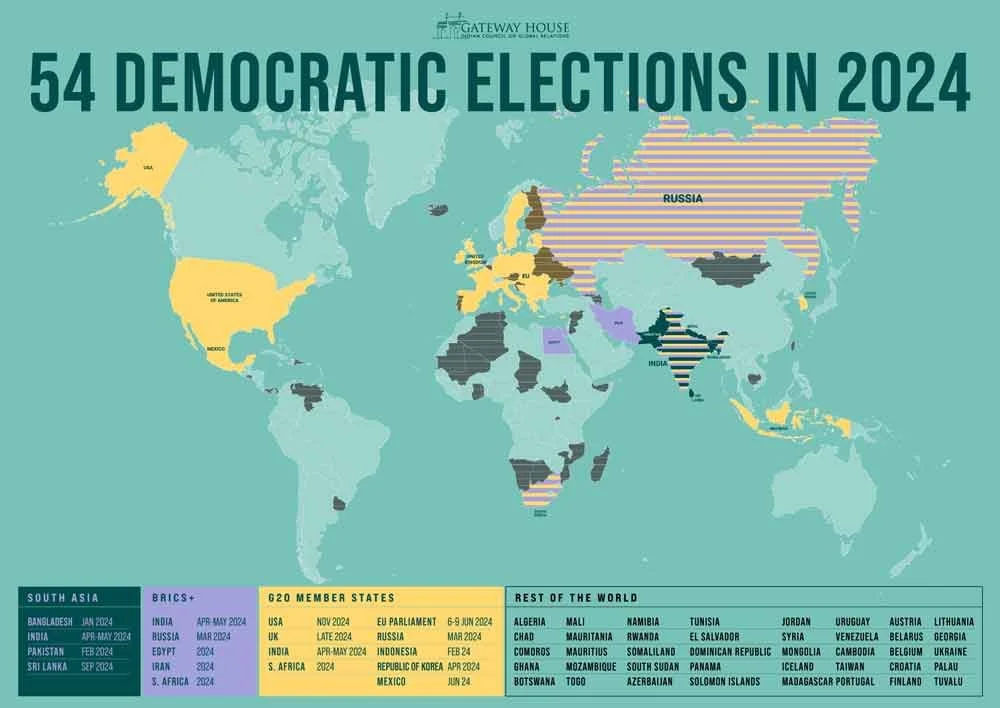

But today, the word "democracy" has such positive meaning that even very different governments claim to use it.

Still, some modern people share Plato’s doubts.

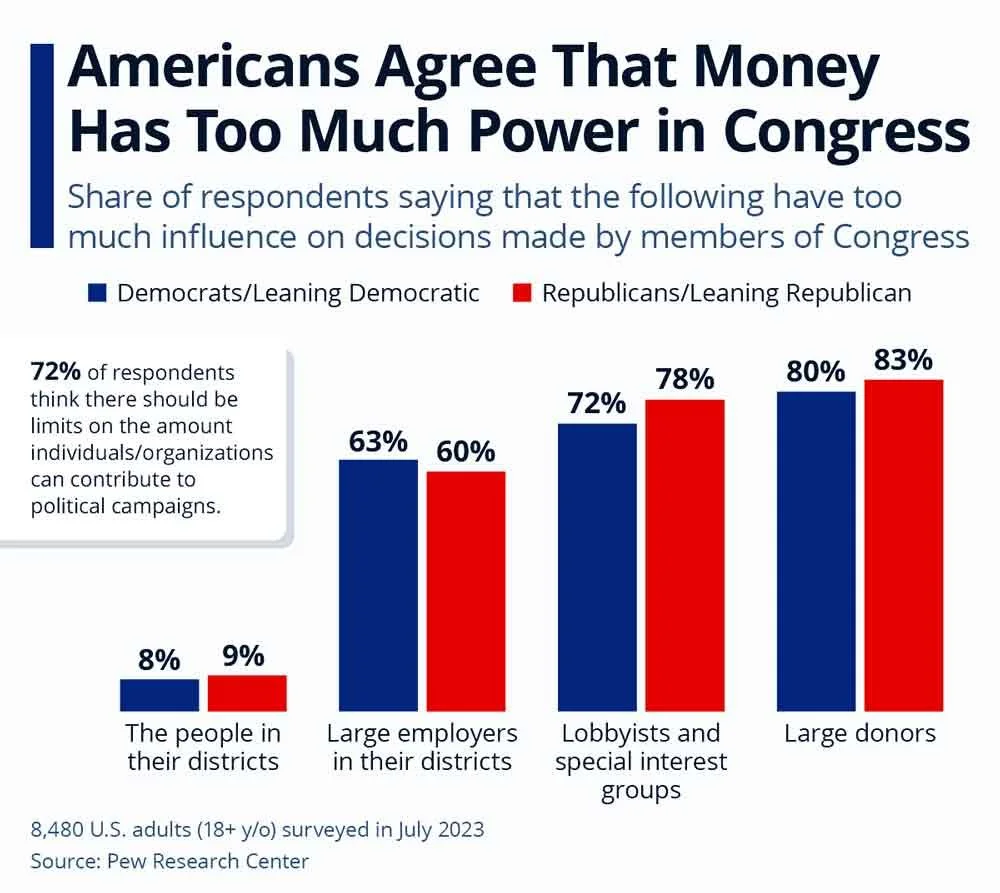

That’s why many democracies today elect leaders who are seen as qualified to make decisions for everyone. But this has its own problems—like the influence of money and the rise of career politicians whose interests may not match those of the people they serve.

Could bringing back sortition lead to a government that’s more diverse and fair? Or is political office, like Athenian military command, a job that needs special skills?

You probably shouldn’t hold your breath to win a spot in your country's government.

But depending on where you live, you might still be randomly chosen to serve on a jury, a citizens’ assembly, or a deliberative poll—all modern examples of how the ancient idea of sortition is still alive today.

x

► COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

— please answer with complete sentences

What is a lottery?

If elections weren’t a big part of democracy in ancient Athens, who served in government?

What kind of democracy they they have in ancient (500 BCE) Athens?

What did the ancient Athenians call their 500-member governing council?

What’s the process of random selection called? (Hint: fancy word ending in -tion.)

What became the duty of all citizens?

Who was left out of Athenian "rule by the many"?

What percentage of the population was eligible to participate in government?

Who criticized this kind of democracy as chaotic and foolish? (Hint: He’s a very famous philosopher.)

What problem do many people see in democracy today?

► From EITHER/OR ► BOTH/AND

► FROM Right/Wrong ► Creative Combination

THESIS — Argue the case that we don’t need elections! Randomly choosing citizens to serve in government is the best democracy!

ANT-THESIS — Argue the case that we need politicians who know what they are doing to serve in government. Elections make the best democracy!

SYN-THESIS — How might these two perspectives be brought together?