“The Grandest Event”

The Boston Tea Party

• Read •

“The Grandest Event”

The Boston Tea Party

Imagine a cold night in 1773, with trouble brewing in Boston Harbor, not just tea1.

This event, which wasn’t actually a party despite its name, was a key moment leading up to the American Revolution.

Trouble Across the Atlantic

In October 1773, seven ships loaded with a favorite drink of the colonists—tea—set sail from Plymouth, England, for various port cities along the North American Atlantic coast.

The cargo on these ships was worth a massive £600,000 ($118–$147 million today).

All of it belonged to the East India Company, a huge British firm that was struggling and on the brink of bankruptcy.

To save the company and raise a needed £90,000 ($17.7–$22 million today) or more in cash, Britain’s prime minister, Frederick, Lord North, had passed a new law called the Tea Act.

This act kept the old tax on every pound of tea sold. But it also lowered the overall price, hoping to undercut American merchants who were smuggling cheaper tea from other places.

The law also gave the East India Company a monopoly on tea sales in the colonies.

Lord North thought his plan was brilliant: it would save the company, slow down smuggling, and quietly set a precedent by including the tax within the lower price.

He doubted the Americans would be unhappy with cheaper tea.

He was very wrong.

Outrage and Resistance

Colonial merchants who made money from smuggling were furious.

Colonial shopkeepers were also upset because they could no longer sell tea to their customers.

But the problem was bigger than just profits. The colonists felt the new law was an "attack upon a fundamental principle of the [British] constitution. The core belief was: no colonist had consented to the tea tax, so no colonist needed to pay it.

Leading Patriots decided on immediate resistance.

People who were supposed to receive the tea shipments were to be convinced—or coerced—to refuse them.

Colonists were urged not to buy or drink the beverage. And the tea crates aboard the arriving ships had to be stopped from being unloaded, for fear that "weak-willed people" would buy it.

Tea Turned Away

When a tea ship reached Philadelphia, a leading Patriot named Dr. Benjamin Rush rallied the city. He warned that if the tea were allowed ashore:

"Farewell American Liberty! We are undone forever!…Remember, my countrymen, the present era—perhaps the present struggle—will fix the constitution of America forever—think of your ancestors and your posterity".

The governor of Pennsylvania was persuaded, and the captain sailed back to Britain with his hold still full of tea.

In Charleston, South Carolina, a mix of "flattery and threats" convinced the recipients of the tea shipments to refuse them. Customs officials seized and stored that tea.

Boston's Obstinacy

In Boston, however, things became much more complicated.

Four ships were originally sent to Boston, but one was lost at sea, leaving three to arrive at Boston Harbor. The first of the three ships arrived on November 28, 1774.

Customs rules demanded that the duty had to be paid within twenty days of the goods landing, which meant by December 17.

Notices soon appeared across the city, declaring the detested tea had arrived and that the "Hour of Destruction or manly Opposition to the Machinations of Tyranny stares you in the Face".

The people meant to receive the tea fled.

Most importantly, Governor Hutchinson refused to let any ship leave the harbor without the tax duty being paid.

John Andrews, a prominent Boston merchant, wrote to his brother-in-law in Philadelphia, keeping him informed. He shared the colonists’ anger but was uneasy about the risk of a mob taking over.

The Night of Action

On the afternoon of December 16, 1773, some six thousand people from Boston and surrounding towns packed into the Old South Meeting House. The next morning, customs officers were planning to land the tea cargoes, and a violent fight seemed certain.

Samuel Adams, the leader of the secret society called the Sons of Liberty, presided over the meeting. When word arrived that the governor still refused to let the ships leave, Adams declared, "This meeting can do nothing more to save the country.”

This seemed to be a secret command.

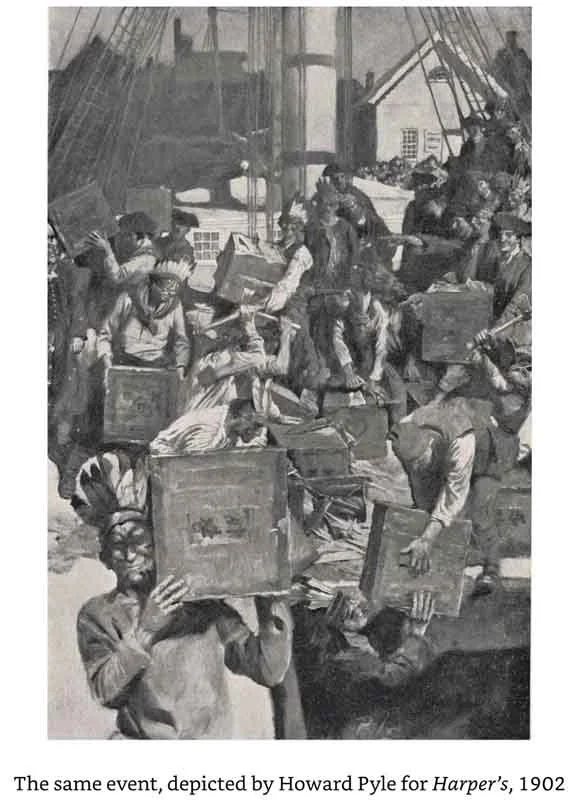

Right away, fifty to sixty men—rich and poor, all crudely disguised as Native Americans—streamed out of the hall, whooping and whistling as they rushed toward Griffin’s Wharf. To hide their identities, they had wrapped blankets around their shoulders and covered their faces with paint and soot.

We know today that 116 people were definitely there, some coming from as far as Worcester in central Massachusetts. Many kept their identities hidden, even going to their graves without telling who they were.

John Andrews and about two thousand others followed them.

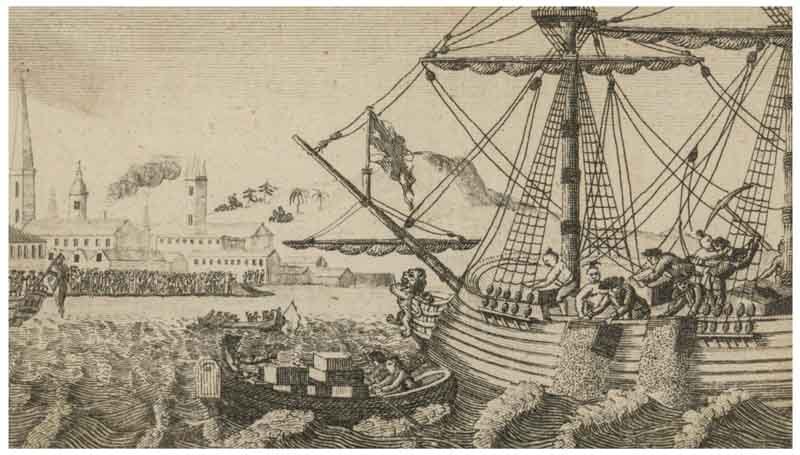

The group boarded the three tea ships tied up at Griffin’s Wharf. In about two hours, using hatchets, they opened 340 or 342 crates of tea and poured the contents—more than 46 tons—into the harbor.

The tea destroyed was worth about £10,000 (approximately $1.7 million today).

Since it was low tide, the huge clumps of tea piled up by the ships could be seen. One of the teas destroyed was hyson, a green tea and a favorite of both Thomas Jefferson and George Washington.

No other property on the ships was damaged. When one participant tried to fill his coat pockets with handfuls of tea, he received a "severe bruising," as Andrews remembered.

John Adams later wrote in his diary that this was "the grandest Event which has ever yet happened Since the Controversy with Britain!".

He was worried, though, about Britain's reaction: "Will they resent it? Will they dare to resent it? Will they punish us? How? By quartering troops upon us?—by annulling our charter?—by laying on more duties? By restraining our Trade? By Sacrifice of Individuals, or how?".

The Aftermath

Adams would soon get his answer.

The King of England was furious and helped pass a law to punish the men who dumped the tea.

As a result of the protest, the British government closed the Port of Boston to all ships on March 24, 1774. The Royal Navy sent warships to patrol the area and stop anyone from going in or out.

The colonists were not allowed to leave Boston until they had paid for all the tea.

This punishment made residents very angry, as they felt everyone was being punished for the actions of only one group.

For many years after the event, it was simply called "the destruction of the tea".

It wasn't until 1829 that the term "Boston Tea Party" was used.

This bold act of defiance was one of the main triggers for the American Revolution, which began on April 19, 1775, just outside Boston. The British kept trying to control the colonies, and the colonies kept rejecting that idea.

Annul (v.): To declare a law or agreement to be no longer valid.

Bankruptcy (n.): A condition of financial ruin where a business or person cannot pay its debts.

Coerced (v.): To persuade an unwilling person to do something by using force or threats.

Complicated (adj.): Involving many different parts or elements; difficult to understand or deal with.

Consented (v.): Agreed to do something.

Consequences (n.): Results or effects of a previous action or condition.

Controversy (n.): A prolonged public disagreement or argument.

Determination (n.): Firmness of purpose; the act of reaching a decision.

Fundamental (adj.): Forming a necessary base or core; of central importance.

Machinations (n.): Evil or complex plots or schemes.

Monopoly (n.): The exclusive possession or control of the supply or trade in a commodity or service.

Obstinate (adj.): Refusing to change one's opinion or chosen course of action, despite attempts to persuade one to do so; stubborn.

Precedent (n.): An earlier event or action that is regarded as an example or guide to be considered in similar later circumstances.

Resistance (n.): The refusal to accept or comply with something; the attempt to prevent something by action or argument.

Unanimous (adj.): Fully in agreement.

Undercut (v.): To offer goods or services at a lower price than a competitor.

► COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

— please answer with complete sentences

How much money did the East India Company need to stay in business?

How much was this in today’s US dollars?

What two groups of colonists were upset with the new Tea Act?

Who was the leader of the secret society called the Sons of Liberty?

What is the date of the Boston Tea Party?

How many tons of tea was destroyed?

What was the value of the tea destroyed in today’s US dollars?

After the raiders three tea into sea, what did John Adams write in his diary?

What did the British Government do to punish Boston?

When did the American Revolution begin?

What was the Boston Tea Party called before 1829?

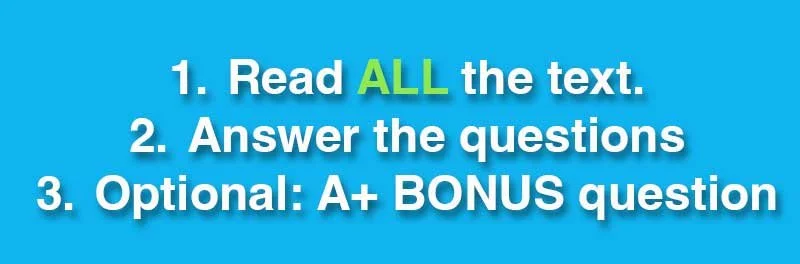

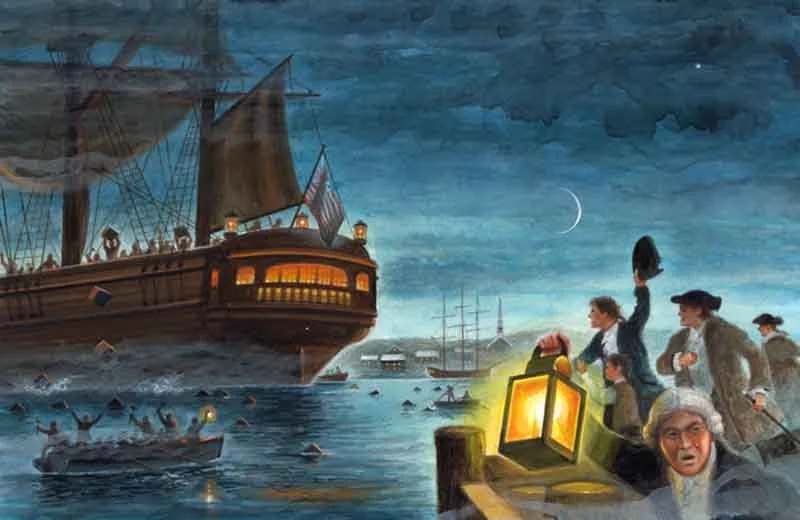

A+ BONUS: Look closely at the illustrations in this text.

Write 5 things you learn about the Boston Tea party from looking at these pictures.