THE COTTON GIN

• Read •

THE COTTON GIN

The Paradox of Invention

This is the dramatic story of an invention that changed the world in ways no one expected.

Imagine a machine that could cut 10 hours of boring, hard work down to just one hour. Picture a machine so efficient that it would free up people to do other things, kind of like how the personal computer changed how we work and play today.

We usually think that great inventions are supposed to make life easier for everyone. But the machine I'm going to tell you about did none of this.

In fact, it accomplished just the opposite and created a massive problem.

• Unintended consequences

Slavery in the Early Republic

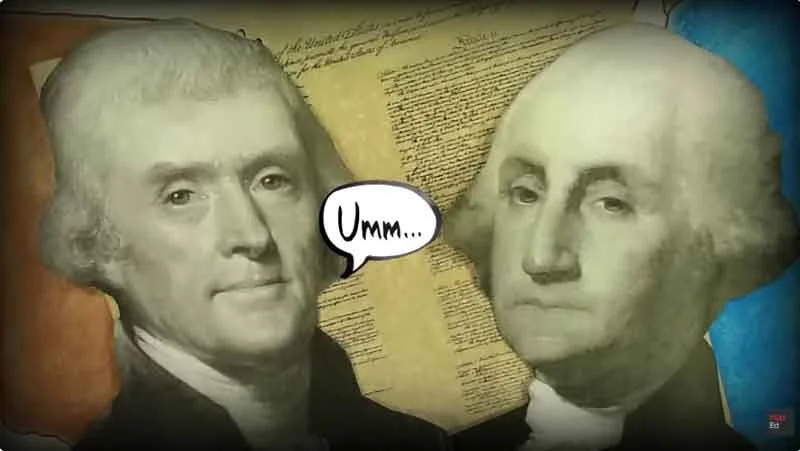

In the late 1700s, just as America was getting on its feet as a republic under the new U.S. Constitution, slavery was a tragic American fact of life.

• 13 American colonies.

It was a time of confusing contradictions. George Washington and Thomas Jefferson both became President while owning enslaved persons, knowing that this peculiar institution contradicted the ideals and principles for which they fought a revolution.

• Washington and Jefferson both owned enslaved people.

They had just fought a war for freedom, yet they held other human beings in bondage.

But both men believed that slavery was going to die out naturally as the 19th century dawned. They thought it was becoming too expensive and unnecessary.

They were, of course, tragically mistaken.

Eli Whitney & the Cotton Gin

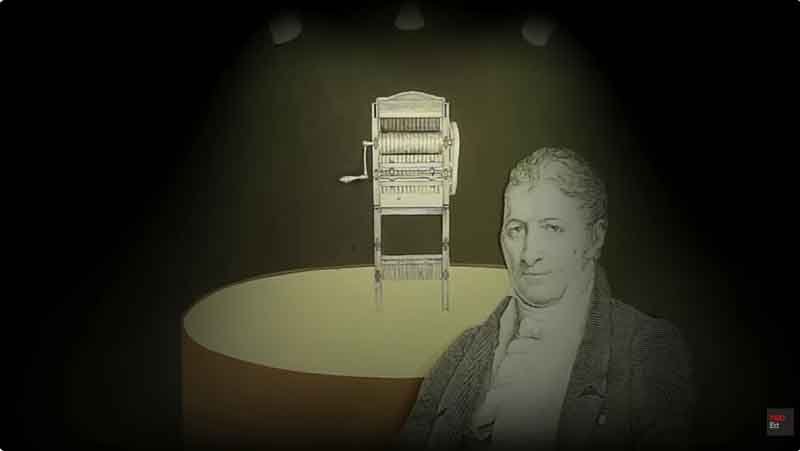

The reason for this mistake was an invention: Mr. Eli Whitney's cotton gin.

• Eli Whitney

A Yale graduate, 28-year-old Whitney had come to South Carolina to work as a tutor in 1793. He was young, educated, and looking for his place in the world.

Supposedly, he was told by some local planters about the difficulty of cleaning cotton.

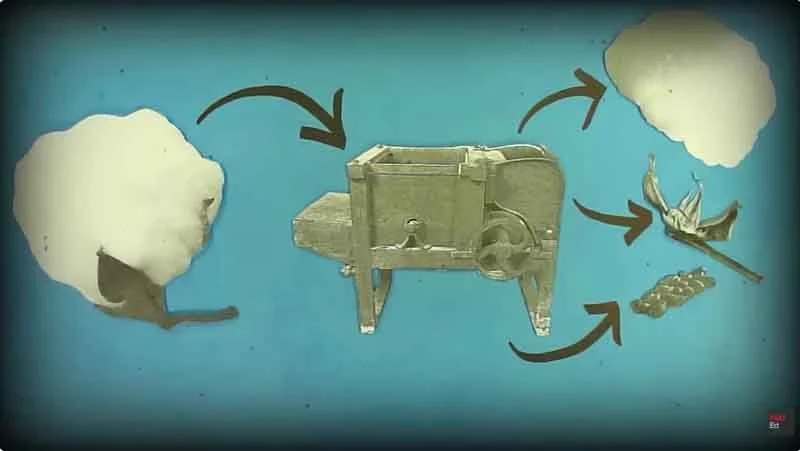

The green-seed cotton that grew easily in the South was incredibly hard to process. Separating the sticky seeds from the fluffy cotton lint was tedious and time-consuming.

• Cleaning cotton is difficult!

Working by hand, an enslaved person could clean about a pound of cotton a day. It was slow, backbreaking work that made fingers ache.

But the Industrial Revolution was underway, and the demand for cotton was increasing rapidly.

Large mills in Great Britain and New England were hungry for cotton to mass-produce cloth. These factories had huge machines that could weave fabric faster than anyone could supply the raw material.

• Large mills in Great Britain and New England were greedy for cotton!

As the story was told, Whitney had a "eureka moment" and invented the gin, short for engine.

• Eureka: a cry of joy or satisfaction when one finds or discovers something

The truth is that the cotton gin already existed for centuries in small but inefficient forms in places like India.

In 1794, Whitney simply improved upon the existing gins and then patented his "invention."

He built a small machine that employed a set of stiff wire cones and teeth that could separate seeds from lint mechanically as a crank was turned. With it, a single worker could eventually clean from 300 to one thousand pounds of cotton a day. It was a mechanical marvel.

The Rise of King Cotton

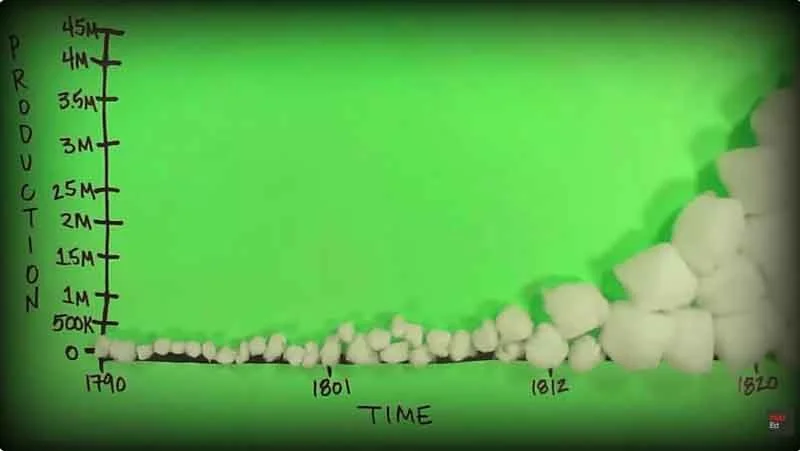

The impact was immediate and staggering.

In 1790, about 3,000 bales of cotton were produced in America each year. A bale was equal to about 500 pounds, which is a massive amount of fluff.

By 1801, with the spread of the cotton gin, cotton production grew to 100 thousand bales a year.

After the destructions of the War of 1812, production reached 400 thousand bales a year.

As America was expanding through the land acquired in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, yearly production exploded to four million bales.

Cotton was king.

This phrase meant that cotton ruled the economy. It exceeded the value of all other American products combined, representing about three-fifths of America's economic output.

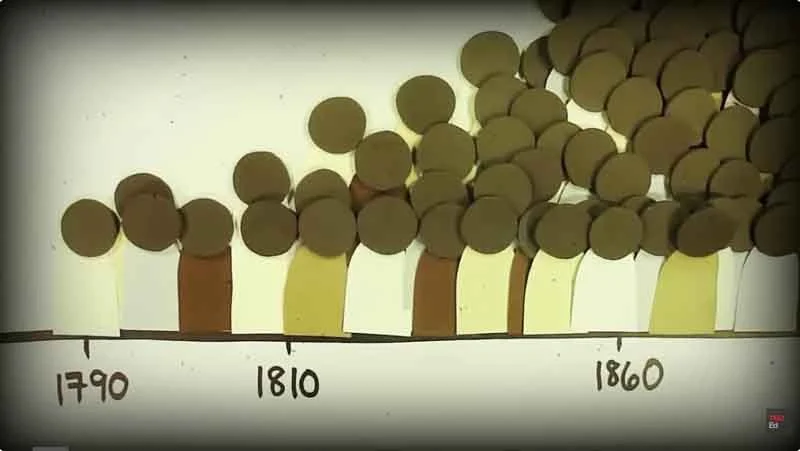

The Human Cost

But instead of reducing the need for labor, the cotton gin propelled it.

This is the sad twist of the story. Because the machine could clean cotton so fast, plantation owners wanted to grow more and more of it.

While the cleaning was easy, the planting and picking still had to be done by hand. Therefore, more slaves were needed to plant and harvest king cotton in the hot sun.

The cotton gin and the demand of Northern and English factories re-charted the course of American slavery.

In 1790, America's first official census counted nearly 700 thousand slaves.

By 1810, two years after the slave trade was officially banned in America, the number had shot up to more than one million.

During the next 50 years, that number exploded to nearly four million slaves in 1860, the eve of the Civil War.

Whitney’s Fate

As for Whitney, he suffered the fate of many an inventor.

He thought his patent would make him rich and protect his idea. However, the machine was actually quite simple to understand once you saw it.

Despite his patent, other planters easily built copies of his machine or made improvements of their own without paying him a dime.

You might say his design was pirated.

Whitney spent years in court fighting for his rights, but he made very little money from the device that transformed America.

Unintended Consequences

But to the bigger picture, and the larger questions.

What should we make of the cotton gin?

History has proven that inventions can be double-edged swords. This means they can be helpful and harmful at the same time. They often carry unintended consequences.

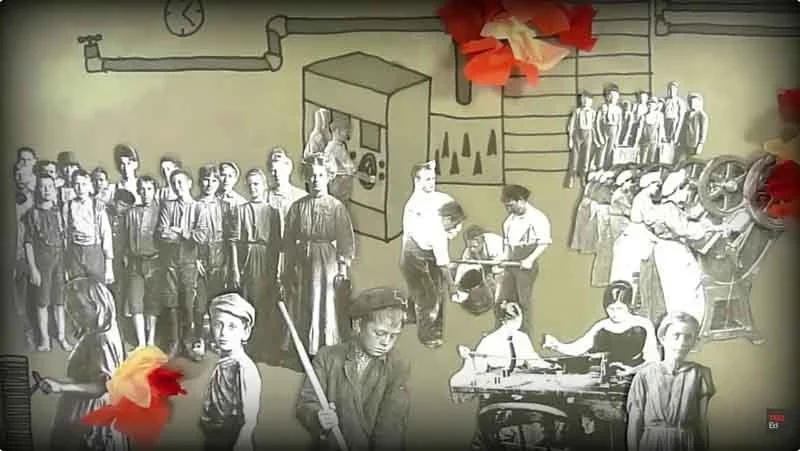

The factories of the Industrial Revolution spurred innovation and an economic boom in America.

But they also depended on child labor and led to tragedies like the Triangle Shirtwaist fire that killed more than 100 women in 1911 due to unsafe working conditions.

Disposable diapers made life easy for parents, but they killed off diaper delivery services. And do we want landfills overwhelmed by dirty diapers?

And of course, Einstein's extraordinary equation opened a world of possibilities for energy and science.

But what if Einstein’s equation also led to the atomic bomb?

We must always look at how new technology changes our world, for better and for worse.

Bale (n.) A large bundle of goods tightly bound together for shipping or storage.

Census (n.) An official count or survey of a population, recording details of individuals.

Contradict (v.) Deny the truth of a statement or act against a specific principle.

Destructions (n.) The action or process of causing so much damage to something that it no longer exists or cannot be repaired.

Double-edged (adj.) Having two cutting edges; having two possible outcomes, one positive and one negative.

Efficient (adj.) Achieving maximum productivity with minimum wasted effort or expense.

Eureka (excl.) A cry of joy or satisfaction when one finds or discovers something.

Innovation (n.) A new method, idea, product, or way of doing things.

Institution (n.) An established law, practice, or custom; in this text, it refers to the practice of slavery.

Mechanically (adv.) By means of machinery or physical forces; done without thought or feeling.

Patent (n.) A government license giving a right or title for a set period, especially the sole right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention.

Peculiar (adj.) Strange or odd; unusual.

Pirated (v.) Used or reproduced another's work or invention without permission.

Propelled (v.) Drove, pushed, or caused to move in a particular direction, usually forward.

Republic (n.) A state in which supreme power is held by the people and their elected representatives.

Tedious (adj.) Too long, slow, or dull; tiresome or monotonous.

Tragic (adj.) Causing or characterized by extreme distress or sorrow.

Unintended (adj.) Not planned or meant.

► COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

— please answer with complete sentences

Name two US Presidents who owned enslaved people.

How did slavery contradict the principles of the American Revolution?

Hint: Look at definition of contradict

Why was cotton difficult to process?

As the Industrial Revolution got underway, who was greedy for cotton?

How much more cotton was processed in 1801 than in 1790?

The cotton gin was supposed to reduce the need for enslaved persons.

It didn’t.

Why not?

How many enslaved people were there in the US in 1790, 1810 and 1860?

More factories brought greater wealth to the US. This was a positive.

What negatives did they also bring?

Einstein’s famous equation changed science for the better.

What negative might his equation have also had?

In your own words, what is an unintended consequence?

A+ BONUS: Watch the video below.

What else did you learn about the cotton gin or the unintended consequences new inventions might bring?